Warsaw, 16th November 2023

Commentary of the Union of Entrepreneurs and Employers on the amendment to the

EU pharmaceutical law

- On 26th April 2023, the European Commission presented draft regulations with the intention to reform EU pharmaceutical law.

- At the EU level, this is the most significant amendment to pharmaceutical law in 20 years.

- The European Commission sets major goals for the regulations in question, among others:

- creating a common market and ensuring universal and equal access to cheap and effective medicinal products for patients living in all European Union countries;

- offering an attractive and innovation-friendly system for research, development, and production of medicines in Europe;

- reducing administrative burdens and substantially speeding up procedures for granting marketing authorisations for medicinal products so that they can reach patients as quickly as possible;

- increasing the availability and ensuring a constant supply of medicinal products to patients, regardless of their place of residence within the EU;

- addressing antimicrobial resistance as part of the EU’s “One Health” approach;

- reducing the impact of the production and consumption of medicinal products on the natural environment.

- On 19th October 2023, during the meeting of the European Union Affairs Committee, Maciej Miłkowski, Undersecretary of State at the Ministry of Health, presented the Polish government’s position on the proposed changes, in which:

- the direction of amendments adopted by the European Commission is approved and the challenges related to the lack of availability of medicines and antibiotic resistance are recognised;

- it is indicated that individual solutions of the proposed package require clarification – so that the goals assumed by the European Commission can be achieved;

- there is a clash in the interests of producers of innovative and generic drugs;

- it is emphasised that the purpose of the provisions under discussion is to increase the availability of medicines for patients, and not to support a given group of entrepreneurs.

- On 17th November 2023, the Ministry of Health planned a meeting of the Group for the revision of EU drug regulations, which – together with industry representatives and social stakeholders – is to discuss the proposed solutions.

Limited availability of medicinal products has become noticeable not only on the Polish, but on the entire European market. All EU member states face the challenge of a shortage of raw materials, increased production costs, logistic problems, and competition from Asian markets.

Therefore, it is vital that action be undertaken to adapt the current pharmaceutical regulations – which have not undergone significant changes over the last 20 years – to the reality of today, present needs and challenges. It is necessary to increase the attractiveness of the European market for producers and distributors in order to encourage them to transfer production to the European Union.

Nevertheless, in spite of noble slogans justifying the implementation of the planned solutions, they appear insufficient. They focus on several areas (primarily on changes in the registration process and to the period of market exclusivity for newly registered products), shifting onto producers the obligation to ensure availability. The incentives offered are virtual (e.g. formal shortening of the product registration process down to 180 days; extending in theory the market exclusivity period) and do not contain any substantial support package or investment incentives for entrepreneurs operating in a market of key importance to the economy.

Concurrently, the planned regulations ignore issues that the industry has been struggling with for years and which would require harmonisation at the European level (e.g. the problem of prompt access to therapy, implementation of a modern distribution chain, medicine deliveries straight to patients’ homes, price pressure from the public payer).

In view of the above, it is necessary to conduct a detailed analysis of the planned regulations in terms of addressing the needs of not only the regulator but, above all else, of patients and the industry, as well as to discuss these needs first with the local regulator and then its European counterpart in order to address them in the proposed regulations.

On 26th April 2023, the European Commission presented draft regulations with the intention to reform EU pharmaceutical law.

Following the adoption of the package of changes to the European pharmaceutical law on 26th April 2023 by the European Commission and the simultaneous commencement of the legislative process in the Council and the European Parliament, we present a position on the project, especially in light of the fact that arguments have arisen in the public opinion that the amendments in question will hinder Europe’s innovation potential compared to other regions around the globe. We kindly inform that we disagree with the claim that the reform of EU pharmaceutical law will weaken the competitiveness of the pharmaceutical industry of the European Union. This is particularly important considering that the deadline for submitting changes to the ENVI Committee of the European Parliament expired in mid-November 2023.

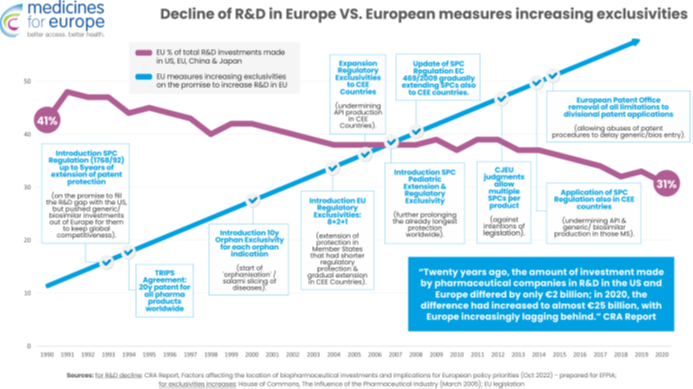

The decline in the global competitiveness of the European pharmaceutical sector in terms of R&D is not related to the erosion of intellectual property, because the EU has consistently increased regulatory incentives and monopolies in intellectual property since the 1990s. Each new intellectual property protection or regulatory protection (TRIPS patents, SPCs, the world’s longest regulatory and market exclusivities, orphan product exclusivity, paediatric exclusivity, and SPC extensions) have been introduced with the specific aim of making Europe a global leader in the field of R&D and innovation.

However, this strengthening of monopoly protections directly corresponds to the relative decline in R&D in Europe compared to China and the US. This proves that the claim that “more monopoly leads to more research and development” is false. To make matters worse, these monopolistic measures have directly contributed to the relocation of medicine production outside Europe, although we applaud the EU’s efforts to remedy this situation through reforms.

On the other hand, policy measures that stimulated competition in the sector of generic medicines have fully lived up to their expectations. Legislation on generic medicines has triggered much-needed competition, doubled access to medicines in Europe, and reduced pressure on healthcare budgets. The regulations for equivalent biological medicines have made Europe a global leader in this technology and contributed to significant investments in the production of biological medicines in the EU.

It is therefore imperative that the “Pharmaceutical Strategy for Europe” continues to aid the generic and biosimilar medicines sector to ensure Europe’s safety in terms of medicines.

In the impact assessment of pharmaceutical legislation, it is highlighted (p. 43) that:

“A direct link between EU incentives and EU competitiveness is hard to establish because while the incentives make the EU markets more attractive, they are agnostic to the medicines’ geographical origin. Around 20% of new medicines authorised in the EU are from the EU, the others are mainly from US, UK, Switzerland and Japan that are equally eligible to all EU incentives. Equally EU based innovative companies can benefit from incentives elsewhere, if they sell their products there.

In June 2016, the Council requested the Commission to conduct an evidence-based analysis of the impact of incentive mechanisms, notably SPCs. Two studies have been commissioned. One from Max Planck Institute questions whether the availability of patent or SPC protection affects companies’ decisions to locate research facilities in one jurisdiction or another, emphasising that other factors are likely of greater importance. The Copenhagen Economics study argued that SPCs could play a role in attracting innovation to Europe, pointing out that taxation, education, and other factors are probably more significant in that respect.”

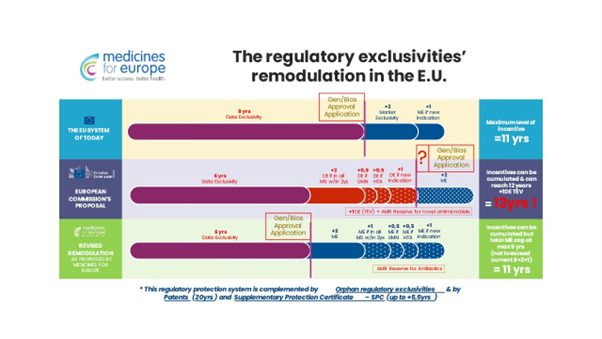

Regulatory exclusivity and exclusivity voucher periods

The pharmaceutical package changes the rules for granting companies the so-called regulatory exclusivity, i.e. temporary protection of entities that introduced a given drug first against market competition. The result of these changes is to extend the maximum protection – which is already longer than, for example, in the United States – from the current 11 years to 13 years.

Regardless, there is no evidence of any correlation between the extension of exclusivity protection and the level of innovation. Data on the directions of import of innovative medicines to the European Union (USA, Switzerland, Great Britain, Japan) prove the opposite.

Moreover, the proposed new rules for granting protection are so unclear that they introduce uncertainty as to when it might be possible to sell a competitive drug in a specific case. One must not forget that the preparation of a generic product requires R&D efforts and clinical trials (bioequivalence studies) and the preparation of registration documentation. The manufacturer of generic products must know several years in advance when they will be able to apply for a marketing authorisation in order to thoughtfully plan the works.

If it suddenly comes to light in the course of these works that data exclusivity has been extended, it may turn out that some of the research carried out or documents prepared (which met the requirements provided for by law on the date on which the six-year data exclusivity period expired) will no longer meet requirement on the date on which the extended data exclusivity period expired. Moreover, during the period of data exclusivity in the EU, generic producers may register medicinal products abroad and sell them there. However, in many countries, the condition for obtaining marketing authorisation is to have a marketing authorisation in the manufacturer’s country. Thus, extending data exclusivity will reduce the competitiveness of producers from the European Union compared to producers from India, China or the USA. In those countries, data exclusivity periods are not as long as they are in the European Union. Therefore, any further additional protection periods should only be granted in the scope of market exclusivity and not data exclusivity.

On top of that, the pharmaceutical package provides for the institution of a Transferrable Exclusivity Voucher (TEV). A company introducing a new antibacterial drug to the market will receive a 12-month-long exclusivity right, which it can use for another drug or sell it to a third party. The proposed structure, although intended to encourage R&D with new antibiotics in mind, may in fact give rise to abuse and anti-competitive behaviour. It is worth considering other methods of supporting the development of antibiotics that have been proposed, for example, in Sweden or the United Kingdom, i.e. an annual revenue guarantee program seems to be an effective tool that can encourage antibiotic developers to invest in research and development by means of ensuring guaranteed revenues. The Swedish and British models show that implementing an income guarantee is a practical and feasible solution that has been tested and has produced positive results.

Even the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) does not identify intellectual property (IP) issues as necessary for relocation of production.

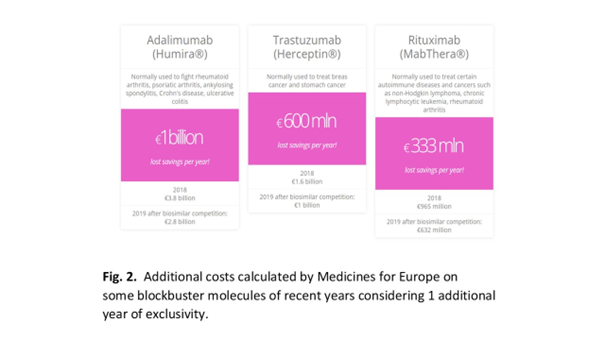

Each year of competition delay means measurable losses for patients and national payers, and one year means a loss of at least hundreds of millions of euros.

In light of the arguments above, we appeal for:

- establishing a maximum uniform period of data exclusivity of 6 years and a basic period of market exclusivity of 2 years, though market exclusivity might be extended by additional periods constituting incentives currently provided for in the draft directive, however, the total duration of registration protection should not be longer than currently applicable periods, i.e. maximum 11 years;

- a clear indication in the regulations, in the event that the extension of data exclusivity or market exclusivity would be dependent on ensuring the availability of the medicinal product on the market for patients, that such availability means not only launching the medicinal product onto the market and ensuring supplies covering patient demand, but also obtaining reimbursement for this medicinal product or supplying the medicinal product to the EU market, or else the withdrawal of the application for reimbursement in any of the Member States should result in the withdrawal of the granted exclusivity;

- abandoning the TEV and replacing it with the Annual Revenue Guarantee Scheme – developed by the EU-Joint Action on Antimicrobial Resistance and Healthcare-Associated Infections (EU-JAMRAI), thus rewarding innovation while promoting responsible consumption of antibiotics.

Changes in the field of environmental protection

While supporting all actions aimed at improving the state of the natural environment, one should emphasise that the European pharmaceutical industry is already obliged to meet the highest environmental standards. Due to changes in the pharmaceutical package, advanced legislative work is currently underway in the European Parliament and the Council in the field of, for example, municipal sewage, which will significantly affect the European pharmaceutical industry producing equivalent drugs (generic and bioequivalent), which will translate into an increase in the costs of producing these drugs.

With this in mind, one should take into account the balance between objectives and assumptions so that they do not become a competitive barrier and do not lead to the elimination of this branch of the pharmaceutical industry from Europe. This is particularly important due to the shortage of essential medicines in Europe and Asian competition which, on the one hand, is financially subsidised by their governments, and on the other hand is not subject to such stringent regulations.

Impact on competitiveness and SMEs

On small and medium-sized enterprises, the impact assessment states:

- In terms of effect on competitiveness, the proposed incentives do not make a geographic distinction, they equally offer regulatory protection for products developed in the EU, or anywhere in the world which ensures a level playing field between EU-based and third country-based companies. While the EU regulatory framework is attractive for developers, competitiveness also depends on many other factors e.g. tax system and incentives; available grants, loans and other funding (e.g. the European Innovation Council Accelerator); pool of talents; proximity of top academia; clinical trials infrastructures; market size; security of supply chains; favourable reimbursement decisions (p. 60);

- Similarly, incentives for UMN would benefit SMEs, which are generally willing to make early-stage investments in areas of high risk, by giving more value to their assets even if they are acquired by big pharma in late-stage development. SMEs already enjoy fee exemptions and reductions for regulatory procedures and through the new horizontal measures SMEs will benefit from optimised scientific support with a greater likelihood of success for authorisation. Overall, with the increasing investment in biopharmaceutical R&D and the increasing share of SMEs among developers, biopharma SMEs in the EU and elsewhere would have excellent prospects for the future (p. 61).

On the one hand, the European Commission is talking about shortening drug exclusivity periods, but on the other, the proposed regulations do in fact open up a whole range of possibilities for extending them. The maximum period of market exclusivity for a drug – of course, apart from the 20-year-long patent protection – according to the new proposed directive and regulation is to be 13 years, while it presently is 11 years.

In addition, the European Commission also proposed the so-called IP package – concurrently processed in the Council and the European Parliament, in which monopoly companies gain the opportunity to introduce one European procedure, SPC, in all EU countries. Today they have to apply member state by member state. And even though the pharmaceutical package introduces regulations shortening registration procedures, enforced in the early 1990s, the SPC intended to compensate for the length of the registration process is not shortened.

To boot, there are numerous projects dedicated to the development of research on new drugs, such as support from EU funds – IPCEI mechanisms or the largest public-private initiatives in the world – Innovative Medicines Initiative, and now the Innovative Health Initiative, in which half of the funds come from all EU citizens and half from monopoly companies represented by COCIR, EFPIA and Vaccines Europe (a specialised vaccines group within EFPIA), EuropaBio, MedTech Europe – and the total budget of IHI for 2021–2027 amounts to EUR 2.4 billion.

All this – critical voices from monopoly companies aside – indicates the EU’s openness and support in this area. It is worth supporting the industry manufacturing drugs that compete on the market with price, because they are the ones that are is short supply in pharmacies. And in this area, EU funds are no longer so generous.

The monopoly period should certainly not be extended, because European patients will have to wait longer for price competition to appear on the drug market, and national payers, including Polish NFZ (National Health Fund), will be forced to bear higher reimbursement costs. Every day that the competition is delayed means a multi-million loss for healthcare budgets.

Find out more: 16.11.2023 Commentary of the Union of Entrepreneurs and Employers on the amendment to the EU pharmaceutical law

ZPP Newsletter

ZPP Newsletter