Warsaw, 23rd July 2021

Memorandum of the Union of Entrepreneurs and Employers on the post-pandemic recovery

of the Polish economy

- Introduction

The coronavirus pandemic that broke out in Q1 2020 led to an unusual recession on a global scale. It was sudden and deep, and left a lasting mark on several sectors of the economy. According to the calculations of the World Bank, the global economy shrank by 4.3% last year. The scale of the recession was milder than it had been assumed at the beginning due to, among other things, the fact that developed countries dealt with the pandemic relatively well.

The pandemic recession affected individual sectors of the economy in various ways. The industries that lost customers due to restrictions on the movement of people were affected most – these include industries such as tourism, food services, air transport, and hospitality. On the other hand, the broadly understood technology industry has benefited from keeping people at home. Certain industries and sectors passed through the worst period of the pandemic in a relatively neutral manner.

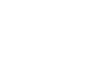

The pandemic also had, of course, a negative impact on the Polish economy, leading to the sharpest decline in GDP since the economic transformation. It amounted to -2.7% last year, and was the worst result of the Polish economy since 1991.

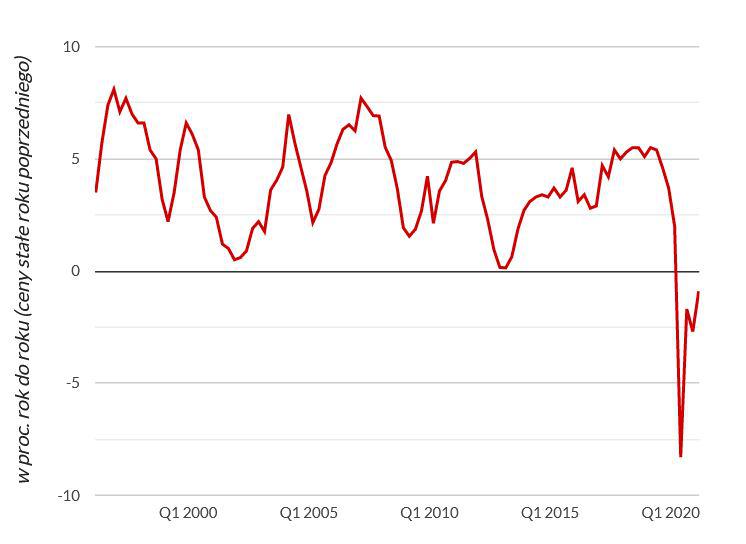

The year 2021 brings a post-pandemic rebound, stimulated by governments and central banks. Governments have launched bailouts totalling trillions of dollars. Central banks have kept rates at very low levels – and even lowered them in numerous cases – thereby offering cheap money and readily available credit.

The GDP growth rate in Q1 2021 turned out to be positive in many of the most important economies. In the US, it was 0.4% year-on-year (hereinafter y-o-y). In China, it skyrocketed to 18.3% y-o-y. In Singapore, it came to 1.3% y-o-y. According to the forecasts of the World Bank, the global economy is to grow by 5.6% this year, which is to be the quickest pace in 80 years. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) claims in turn that it will grow by 6%, and then the growth rate will become slightly moderate in 2022 (4.4% y-o-y). This is without any doubts an effect of a low base, but some readings suggest that optimism has returned to the world economy. Let us have a look, for instance, at the IHS Markit Eurozone Manufacturing PMI – the index of the economic situation in the manufacturing industry in the euro area – which reached in June this year historic highs (63.4 points), after 12 months of increases.

How does the Polish economy compare to others? What does the pandemic rebound in our country look like? Which industries are recovering faster and which ones slower after last year’s recession? How do the phenomena taking place in our main trading partners (e.g. demand shifts) affect selected sectors of the Polish economy? The next wave of the pandemic, possibly to emerge in autumn this year, how destructive could it be? This study tries to earnestly answer these important questions.

- Rebound of the Polish economy at the beginning of 2021

In Q1 2021, Poland’s real gross GDP (that is, inflation-adjusted) was higher by 1.1% than in the previous quarter according to Statistics Poland (GUS). However, year-on-year, it decreased by 0.9%. (data not adjusted seasonally), which turned out to be a better result than economists expected (the forecast mentioned an increase by 0.9% quarter-on-quarter and a decrease by 1.2% y-o-y).

Investment expenditures positively surprised in Q1 2021 (increase by 1.3% y-o-y, while an 8.6% drop was expected after dropping by as much as 15.5% in Q4 2020). Private consumption increased by 0.2% y-o-y, while a decline was expected. Exports increased by 5.7% y-o-y, and imports by 10%.

How did the Polish economy compare to others in Q1 2021? The economy of the euro area shrank by 1.3% y-o-y (forecast: -1.8%), so it fared well compared to developed European markets. Also compared to other countries of the region, it did quite well, because the Czech economy, for example, shrank by 2.1% y-o-y, while the Lithuanian and the Slovak grew by 1.2% and 0.2% y-o-y respectively.

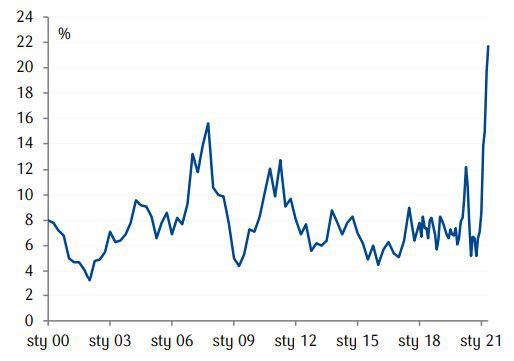

Poland – GDP growth rate y-o-y

[% year-on-year (stable prices of the previous year)]

Source: SpotData / Puls Biznesu

Median of Poland’s GDP growth forecasts in 2021

[% year-on-year]

Source: SpotData / Puls Biznesu

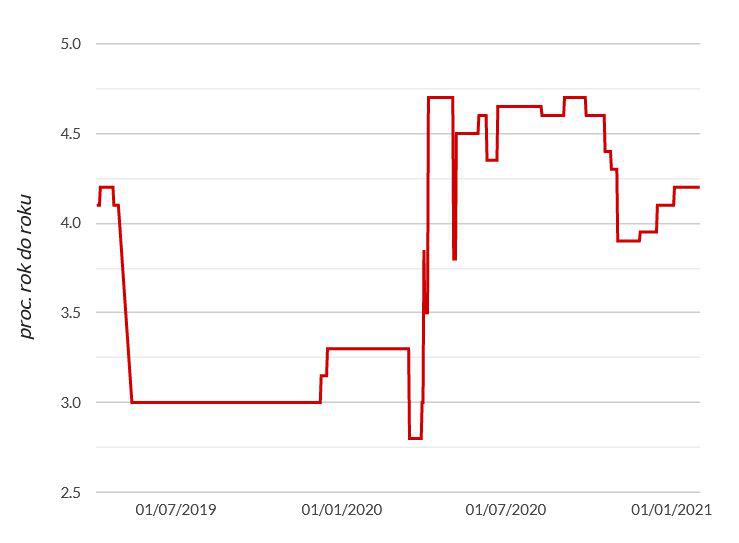

Data on the Polish economy in May this year turned out to be very good. May was the first month that the economy fully opened after the winter/spring restrictions. Retail sales in May rose in real terms by 13.9% y-o-y after an increase of 21.1% y-o-y a month earlier, and – in nominal terms – it increased by 19.1% y-o-y. Construction and assembly production increased 4.% in May y-o-y against -4.2% y-o-y in April. Sold industrial production increased by 29.8% in May y-o-y after an increase of 44.5% y-o-y in April (which resulted from the low base for April 2020). Therefore, one can see that the domestic economy is in the phase of rapid economic growth, and the construction industry is chasing sales or trade.

Poland – level of activity in the economy

[Index, January 2020 = 100 retail sales industrial production construction production]

Source: PKO BP Analyses Centre

In this case, what are the forecasts for Q2 and the entire 2021? According to economists at PKO BP, the GDP growth in Q2 amounted to approx. 10% y-o-y, and throughout the year the reading may exceed 5.1% (e.g. due to a revival in investments). According to economists at Bank Pekao, GDP in Q2 could have grown in double-digit terms (approx. 11% y-o-y), and for the entire 2021 it will grow by over 5%. According to the economists at Credit Agricole, the period of shrinking of the Polish economy came to an end with Q1 2021, because in the quarters to come the “base effect” will take effect – exports and consumption will grow. In turn, the Polish Economic Institute (PIE) forecasts that the Polish GDP growth rate this year will amount to 4.4%, mainly due to the effect of delayed demand. The European Commission raised its economic growth forecasts for Poland for 2021 in early July from 4% up to 5% in its own forecast, while the Union of Entrepreneurs and Employers forecasts an increase of 4% in 2021 and 5.1% in 2022.

The dynamic economic rebound – not only in Poland, but around the world – results in a significant increase in the demand for raw materials, which creates price pressure. The so-called non-financial barriers to business appear. In May, the indices of delays in deliveries, production costs, and prices of finished goods reached record highs, whereas the employment, semi-finished stock, and production backlog indices were close to their maximum levels. The data shows a high demand for labour, which, combined with production backlogs, results in insufficient processing capacity, which means that there is need for investment.

Business barriers – shortage of raw materials, materials, and semi-finished products (due to non-financial reasons)

Source: PKO BP Analyses Centre

- Dynamic rebound in certain sectors – manufacturing industry, transport, and trade

As the pandemic recession began last year, economists wondered what shape it would take on as the rebounded afterwards – whether it would be V-shaped (deep crisis, quick rebound), W-shaped (series of recessions and rebounds) or L-shaped (a long-term recession). Today we know that none of these scenarios took place, as the K-scenario took over. This means that certain industries and sectors have quickly and dynamically emerged from the pandemic recession, while others are still in an unenviable situation.

The manufacturing industry, transport, and trade are the best survivors of the pandemic recession, and are recovering the fastest from it. Sold production of industry in Q1 2021 was 7.8% higher than a year ago (when an increase of 0.9% y-o-y was recorded). In May, sold industrial production increased by 29.8% y-o-y, after it skyrocketed by 44.5% in April y-o-y. The Polish manufacturing industry is a beneficiary of the recovery in the global economy.

It is worth taking a look at the export results from Q1-Q2 2021. From January to April, total exports amounted to EUR 90 billion (+19 percent y-o-y) according to GUS. In April, exports of goods increased by 69.2% y-o-y compared to 27.7% y-o-y in March, and in May by 41.7% y-o-y. These double-digit results from April and May are an effect of a low base, but also a display of the strength of demand for Polish goods. Importantly, such results were achieved by Polish exports in connection to the accelerating German economy, our main trade partner.

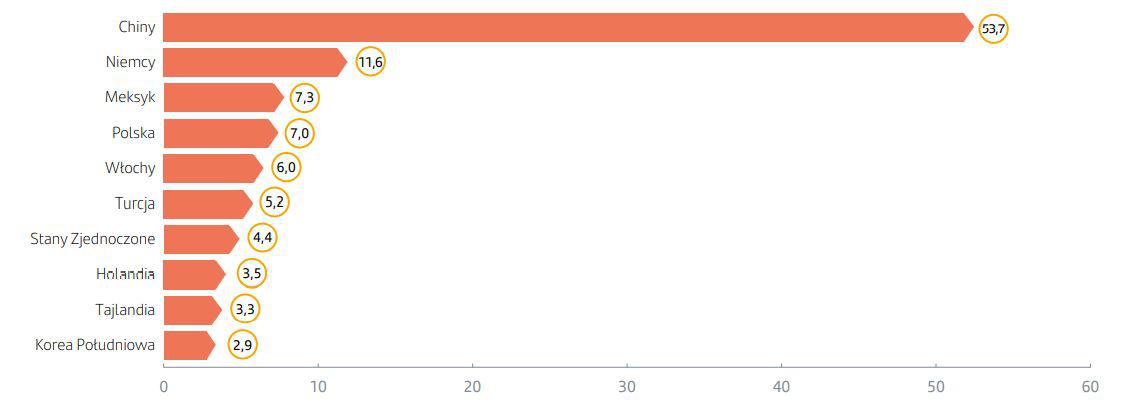

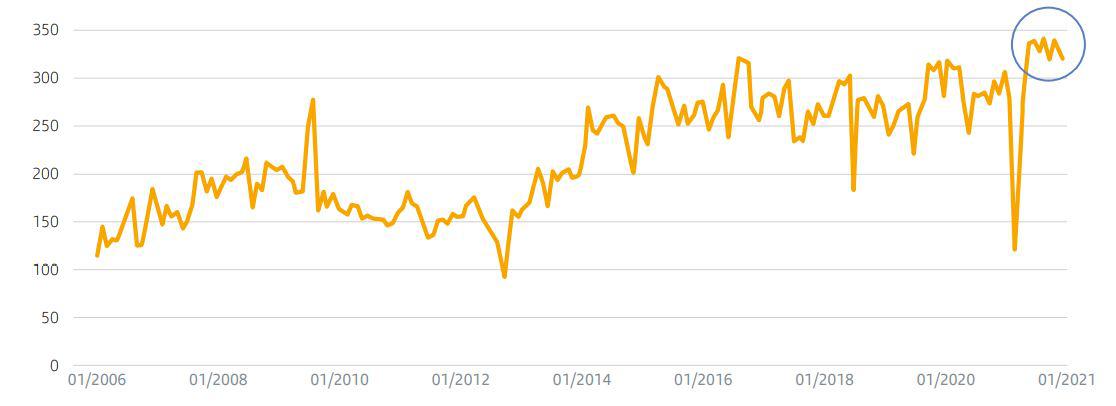

The demand for car batteries, TV sets, catalytic converters, clothes and furniture produced in Poland is high and growing. The export-oriented automotive industry has a great influence on the excellent results of the industry. Producers of food, plastics, and metal products can also boast a high contribution. Producers of electrical devices, who sell most of their production abroad, also do not disappoint according to GUS and PontInfo data. It is noteworthy too to pay attention to the production of household appliances: according to the report “Household appliances manufacturers and suppliers in the face of new trends and challenges” (“Producenci i dostawcy AGD w obliczu nowych trendów i wyzwań” by Bank Santander and SpotData, May 2021) Polish producers satisfy approx. 2% of the global demand, and this increased in the pandemic due to the phenomenon of expenditure substitution (consumers saved on entertainment, so they decided to replace their old washing machines or refrigerators).

10 biggest household appliances exporters (billion USD)

[China, Germany, Mexico, Poland, Italy, Turkey, United States, the Netherlands, Thailand, South Korea]

Source: Bank Santander / SpotData

Refrigerators and freezers – production in Poland (thousand)

Source: Bank Santander / SpotData

However, the industry faces a challenge: supply constraints make production not keeping up with the dynamically growing orders. A great example is the shortage of semiconductors, which has been a big deal in recent weeks, also due to the problems of Tesla. At the same time, in Poland, there are no problems in the automotive sector so far, because vehicle production in May sared by as much as 103.9% y-o-y, after an increase by 370% in April (this was due to an extremely low base).

Trading companies have very good prospects. Private consumption in Q1 2021 increased by 0.2% y-o-y, compared to a decline of -3.2% y-o-y in Q4 2020). Retail sales in May rose in real terms by 13.9% y-o-y, after an increase of 21.1% y-o-y in April. In May, textile sales increased by 92.2% y-o-y and sales of furniture, electronics and household appliances increased by 30% y-o-y.

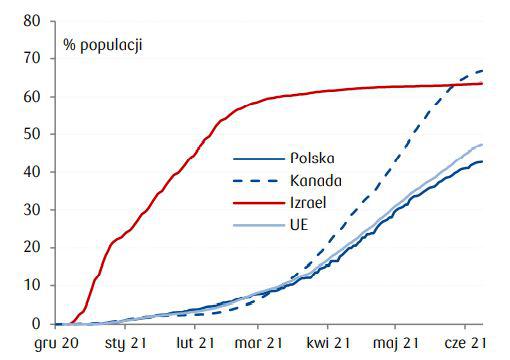

Furthermore, PKO BP data from payment cards show that in April 2021 consumer demand was under the pressure of anti-pandemic restrictions, but at the beginning of May – along with the opening of the economy – it literally exploded and remained at a high level in the following weeks. Savings of households “forced” by pandemic lockdowns amount to around PLN 85-102 billion, which correspond to 6.5-7.8% of private consumption in 2019. During the pandemic, the savings rate of Poles increased from 3% to in 2019 up to 10% in 2020. Consumers in countries that are leaders in vaccination, such as Israel or Canada, spend a lot after the restrictions were lifted, and Poles will probably do the same.

In 2021, the transport industry is gaining momentum. Transport companies in Q2 2021 evaluated their situation as the best in 30 months – this is indicated by the EFL Barometer reading for the transport industry at 65.6 points (+10.4 points quarter-on-quarter) reflecting optimistic forecasts for investments and sales.

- How are those most affected by pandemic restrictions doing – services, hospitality, and tourism

Let us now have a look at the industries and sectors that were hit the most by the pandemic and the restrictions that followed. It is mainly the broadly understood services sector – tourism, HoReCa, and the event industrt (concerts etc.) in particular. Its activity for a large part of 2020 and in Q1 2021 was very limited, and people were reluctant to travel or make use of attractions drawing larger numbers of people (such as aquaparks, ski sloped, and restaurants). Furthermore, companies have significantly reduced the number of business trips.

The contribution of the hotel and food services sector as well as cultural activities to the annual GDP growth in Q4 2020 amounted to -0.9 and -2.0 percentage points respectively according to GUS. In Q1 2021, in hotel and food services sector, added value decreased by 77.2% y-o-y (almost as much as in Q2 2020: -78.4% y-o-y), and for the first time in almost a decade, the number of entities in the tourism industry removed from the National Court Register exceeded the number of new companies. Nearly 80 companies disappeared from the Polish tourism market in Q1 2021, and another 185 were suspended, the operation of nearly 500 hotels and accommodation facilities was suspended (+50% y-o-y) according to Dun & Bradstreet.

“In Q4 2020, the profitability of the hotel industry amounted to -83.6%, and of the food service industry to -6.0%. Revenues were respectively 65% and 15% lower y-o-y (companies with 49+ employees). According to the Polish Hotel Industry Chamber of Commerce, the number of closed hotels increased to 17% in March 2021, and 8 out of 10 open facilities recorded an average occupancy rate well below the break-even point. The moods of 62% of surveyed hotel operators in March 2021 are more pessimistic (+10 percentage points) than a month ago. In the Corona Mood report by Gfk, it was stated that 8% of food services establishments closed down for good and 25% suspended their operations,” say analysts of PKO BP.

One ought to add that the service industry is very sensitive to the administrative risk that still looms over it due to the pandemic. A perfect example is the sudden decision to introduce a mandatory 10-day quarantine from 24th June for all people coming to Poland from non-Schengen and non-EU countries. This restriction was introduced by the legislator with a vacatio legis of mere few hours, which outraged the tourism industry, and was obviously a blow to business, as it reintroduced uncertainty among tourists in terms of planning holidays outside of the EU.

The HoReCa and tourism industries are not doomed to fail, because the demand for their services will soon exceed the reduced supply, and the margins on these activities may be very high in the short term. However, it cannot be denied that companies in this industry may be forced to scale up their operations according to the principle of “grow or die”. Moreover, there are signs that these industries are facing an employee-related problem, as they reskilled in search of stable income and stabilsation during lockdowns, and found alternative employment in other sectors.

- Autumn wave – a threat to economic recovery?

How will the Polish economy fare throughout 2021? Is there a chance for a positive GDP growth rate, even if another wave of COVID-19 appears in the autumn, and with it further restrictions in socio-economic life?

The vast majority of economists are optimistic as to how Poland will handle economic activity in the coming months. The World Bank assumes that the Polish economy in 2021 will grow by 3.8%, that is faster than, for example, the Russian economy (3.2%), but still well below the average growth rate of the world economy (5.6%) or the emerging economies (6%).

“Despite the next wave of the pandemic and the long-term shutdown of many of the largest EU economies, Poland’s return to the pre-pandemic GDP level will be possible already at the beginning of 2022,” said Beata Javorcik, Chief Economist at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, in an interview for “Obserwator Finansowy” in April this year.

According to economists at Bank Millennium, the economic losses for 2020 will be made up for already this year.

“The worsening of the pandemic and the related sanitary restrictions will slow down the GDP growth in Q2 2021. Our baseline scenario is the stabilisation of the epidemic within that quarter, which seems realistic given the announced clear acceleration of the vaccination process, as well as the natural increase in the immunity of this part of the society that has been infected with the coronavirus. (…) The economy will be fuelled by consumption and exports, although as uncertainty subsides, corporate investment should also enjoy revival,” economists of Bank Millennium stated in the publication “Makro i Rynek. Oczekiwanie na letnie ożywienie”(April 2021).

Assuming that Polish businesses have already developed measures under the restrictions, and that at the end of the year, the majority of Polish society will have been vaccinated, on can say with a high degree of probability that each subsequent possible wave of COVID-19 will to a decreasing extent interfere with economic activity (as long as vaccines are effective, and possible SARS-CoV-2 mutations are not more aggressive and resistant). Of course, we are talking about activities in those industries and sectors that do not run businesses based on – or requiring – people to gather in a relatively small space. During subsequent quarantines, companies from the hotel industry or broadly understood entertainment (sports events, concerts etc.) may again be affected. Meanwhile, the industrial or commercial sector should operate increasingly efficiently during possible lockdowns, within the already developed rules of conduct, habits, and security measures.

This means that most industries, and the Polish economy as a whole, should be doing ever better in a prolonged pandemic. Therefore, it may be possible to avoid a classically defined recession – that is, a decline in GDP for at least two consecutive quarters. However, it is not completely out of the question, nor is just one quarter with a decline in GDP (it may be Q4 2021 or Q1 2022). At the same time, taking into account the base effect, the occurrence of a recession in the winter of 2021/22 would have to be associated with a significant reduction in economic activity, for instance due to the emergence of a dangerous and/or aggressive mutation of the coronavirus.

Number of people who received at least one vaccine dose

[Poland, Canada, Israel, the European Union]

Source: PKO BP Analyses Centre

- Summary

The driving force of the Polish economy during the post-pandemic recovery are – and it is not a big surprise – exports, whose dynamics is high and corresponds to what is happening in the global economy. The Polish economy currently benefits from a dense network of connections not only with the German economy, but also with economies from around the world (the United Kingdom, the Czech Republic, the Russian Federation and the US). One can assume that the position of Polish exporters will strengthen as a result of the pandemic – especially within the eurozone.

In some industries and sectors, the rebound is dynamic, as if they were using some kind of “trampoline”, built primarily on global demand. This phenomenon chiefly concerns the manufacturing industry and production companies (especially those that carry out most of their sales abroad). But not all of them are able to use the trampoline, and in fact remain in quarantine – here we should indicate particularly the broadly understood services and entertainment industries.

The situation on the labour market is good (unemployment is at 6.1%), although certain sectors of the economy may be affected by a shortage in workforce. Food services and tourism could be mentioned in this context, because people working in these sectors during lockdowns were, in a way, forced by their life situation to reskill.

Obviously, it is not that such a dynamic rebound will last forever. The first cracks are appearing, and the threats to the prosperity are already to be spotted on the horizon. First of all, one should bear in mind the issue of the fourth wave this autumn, related to the spread of the so-called Delta variant. It is worth emphasising here, however, that only in a negative scenario – assuming the appearance of a dangerous and contagious mutation of the coronavirus, which would force further “hard” lockdowns – one can expect another recession within the Polish economy in the coming quarters (and thus further blows to trade and services). The baseline scenario should assume effective vaccinations and the acquisition of herd immunity as well as economic growth, possibly a quarter with negative GDP. The optimistic scenario should in turn assume a permanent, or even solid, economic growth, among other things, due to an excellent global economic situation and very high savings of households, which will directly drive trade and, indirectly, other sectors of the economy.

However, the coronavirus and the possible autumn lockdown are not the only “black clouds on the horizon”. It is enough to indicate in this regard the issue of shortages of some raw materials or semi-finished products (this may be a blow to industrial companies), and the issue of price pressure (a global boom raises the prices of raw materials). Moreover, a shift in the demand structure in the West is likely to come – consumers will adjust their interest from goods to services. There are regulatory risk factors hanging over the service and tourism industry (as shown by the example of the sudden introduction of a 10-day-long quarantine for people coming to Poland from non-Schengen countries).

Therefore, the post-pandemic jumping on the trampoline may end quite quickly. Nevertheless, one should hope that even if the pandemic continues, the economy will not revert back to recession, as the extent of consumers’ and companies’ adaptation to a changed reality will be significant.

ZPP Newsletter

ZPP Newsletter