Warsaw, 20th November 2023

Memorandum of the Union of Entrepreneurs and Employers on proposals of amendments to European Treaties: A blow to Poland’s competitiveness and while a step towards a European state, the road ahead is still very long

- The report of the European Parliament Committee on Constitutional Affairs (AFCO) on the proposals of amendments to European treaties should be considered in the context of a long-standing discussion on the directions of the European Union’s evolution, in which concepts of federalisation are pushed forward as well as those that preserve the hegemony of the so-called the “Old Union”, Germany and France in particular;

- The proposed amendments to treaties aim to limit the roles played by the European Council and the Council of the European Union as bodies created directly by representatives of EU Member States, while significantly strengthening the European Parliament. Abandoning the principle of unanimity, as well as changing the rules for determining simple and qualified majorities, along with further structural reforms, will not result not in solidifying the position of the strongest players in the EU, but in strengthening it.

- Combining the aforementioned amendments with the expansion of the scope of EU competences, also in economic areas, as well as the introduction of references to agreements and documents that are not yet directly binding (such as the European Pillar of Social Rights or international climate agreements) into treaties, will lead bring about the weakening of competitiveness of the Polish economy. The desire to decouple – implicitly stated in the report – with regard to China, but also Poland’s key partner, the United States, is yet another threat.

- The procedure for amending treaties is difficult, so the AFCO report is not expected to lead to actual changes in primary law. At the same time, due to the fact that it is part of a broader discourse that has been going on for years, one should expect attempts to push for similar solutions in a manner that does not require amending the treaties, as well as the return of the concepts included in the resolution, particularly in the context of possible enlargement of the EU with Ukraine and the Republic of Moldova in mind, among others.

- Political background of the discussion on treaty changes

The European Union is a specific structure (sui generis), which escapes traditional typology. Its uniqueness is best demonstrated by the fact that no analogous entity exists – all others brought up in this context (either the Hanseatic League or the Holy Roman Empire) had existed in the period preceding the emergence of modern nation states. The lack of a relevant development pattern makes attempts to discuss the future of the European Union even more intense.

At the dawn of integration, the above-mentioned problem did not exist in practice. In practice, the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) had one key, strictly political goal: mitigating the risk of a resurgence of German industrial power, and at the same time alleviate the post-war Franco-German tensions so deeply rooted in history. The economic aspect resulting from the 1951 Treaty of Paris, as well as from the name of the new entity itself, related to the creation of a common market for raw materials was rather secondary in this system, especially since the countries that made up the ECSC, as the future showed, did not abandon more or less direct forms of subsidising their own industries or controlling prices[1].

Apart from the practice of applying the Treaty establishing the ECSC, the adopted formula of maintaining relative political stability in Europe (at least in the West) proved successful. For this reason, it began to be developed relatively quickly with additional countries joining the community. These integration-related processes can be described as deepening and broadening. The former served in the long-term to achieve positive economic effects (and successfully so: while in 1960 over 60% of the foreign trade value of member states of the European Economic Community concerned relations with third-party countries, three decades later the proportions were reversed and over 60 % of the value of international trade originated from intra-EEC turnover[2]). With the accession of Spain and Portugal to the European Community in 1986, Western Europe in its entirety became united – the latter was therefore associated with a natural turn towards the centre of the continent. Following the 1989 Autumn of Nations, Central and Eastern European countries became openly interested in the deepest possible integration with Western structures. Among other things, geopolitical conditions secured reciprocity.

After the so-called the fifth enlargement of the EU as well as following the Maastricht Treaty and (above all) Treaty of Lisbon, the Union has found itself in a unique moment. The objective outlined at the very beginning of integration has generally been achieved and not only has Europe ceased to be ravaged by large-scale armed conflicts, but also the economic ties connecting individual countries making up the EU have become so strong that – in the spirit of the Schuman Declaration – any and all military tensions between them have simply become unprofitable. At the same time, following the post-Cold War period of the global unilateral model with a dominant role of the United States, the growing importance of China, but also of some southern countries such as India, and the preservation of a backward, inefficient, but nevertheless strong Russia, resulted in a certain adjustment in favour of multilateralism. This perspective certainly encourages some politicians to think of the European Union as a superpower sitting at the table with the others – especially since none of the European countries individually has as of present the necessary potential to achieve such a status on their own.

The prospect of a global reshuffle therefore determines (at least in narrative) a general direction of changes within the EU, i.e. towards an (at least) increasingly closer cooperation. There is another game taking place at the same time: who will play first fiddle in a potential European superpower. In spite of the numerous enlargements of the EU, the core of its power remains inclusive to a small degree.

No President of the European Commission in history, and no High Representative for Foreign and Security Policy have ever come from a country that joined the EU (the EC back in the day) later than 1986. While positions of commissioners are awarded with country-of-origin parity in mind, this principle does not apply to directorates-general, which are in fact EU equivalents of ministries that implement activities within specific portfolios which individual commissioners are responsible for. With respect to the current term and directorates key from the point of view of economy (AGRI, BUDG, CLIMA, Connect, COMP, ECFIN, EMPL, ENER, ENV, GROW, RTD, TAXUD, TRADE), the overrepresentation of the so-called “Old Union” is downright blatant. Out of 38 people in the management in the above-mentioned directorates, as many as 31 come from EU member states predating the 2004 enlargement. As many as ten people, over a quarter of the management, are citizens of Germany or France. An analogous situation can be observed amongst chairpersons of European Parliament committees. In key economic committees (DEVE, BUDG, ECON, EMPL, ENVI, ITRE, IMCO), out of 34 chairpersons, 25 represent countries of the “Old EU”, and as many as 20 come from just 6 countries: Germany, France, Italy, Belgium, Portugal and Spain.

The above phenomenon is by no means new. According to a ranking published by the Bruegel Institute in 2015, almost 50% of top ranked positions in EU institutions were then taken by Germans, Italians, the French, Spaniards and Belgians, with a distinctly higher representation of the first nation[3]. As of today, representatives of the above-mentioned nations constitute the majority of European Commission staff[4]. There are almost as many Belgians in the European Commission as representatives of all the countries that joined the EU in 2004 combined. Surely this has a completely natural justification from a geographical and logistical perspective, but the fact remains that in European structures (especially at higher administrative levels) the national composition has considerable political significance.

The evolution of the European project takes therefore place in two intersecting planes: one covering the changing role of Europe in the modern world, the other defining the dynamics of power and decision-making within the EU, also in the context of expanding the community with new members. One may wonder whether, in practice, the first plane is not only an external story justifying the push for solutions as part of the real interplay of interests within the second plane. Regardless of the actual situation, however, it is also a fully legitimate and necessary lens for assessing and forecasting the directions of the EU’s evolution.

The above-mentioned planes are purely political in nature, but they cannot be analysed in complete isolation from the contradictory sentiments of the European demos (total population). Changes in the distribution of competences between EU institutions and member states come across real tensions between two strong values: their sovereignty and scope of freedom on the one hand, and the need for effective creation and implementation of policies at the community level (which brings us to the sense of a union itself) on the other. Intuitively, we can assume (because there is no research on this matter) that, for example, most Poles are in favour of the so-called “Europe of homelands”, while some Western societies are with increasing frequency beginning to prefer a federal scenario (one of the ten priority changes proposed for the French contribution to the Conference on the Future of Europe by this country’s citizens was the pursuit of a federation of European states with “strong competences in areas of common interests”[5]).

A discussion covering all the above vectors has publicly re-emerged as a result of the report adopted in October by the European Parliament’s Committee on Constitutional Affairs regarding the proposals of the European Parliament to amend treaties[6].

In the context of the considerations above, it is not without significance that in the group of rapporteurs on this matter there are four Germans and one Belgian, whereas some of the key proposals contained in the report – in particular those regarding the issue of limiting the principle of unanimity in Council votes – correspond to the recommendations from the report “Sailing on High Seas: Reforming and Enlarging the EU for the 21st Century” published this year by the Franco-German working group of experts[7]. Meanwhile, both the French president and the German chancellor, at a completely official level, are in favour of a more tightly integrated European Union. The concept of “European sovereignty” advocated by Emmanuel Macron (mainly boiling down to the fact that Europe as a continent could independently “choose its partners and shape its own fate”, independently from other global powers[8]) is perfectly aligned with Olaf Scholz’s “geopolitical Union” finding its place in a multipolar world[9].

As has already been observed, both France and Germany can count on a more than reliable representation in key EU institutions. If we add their obvious economic advantage (to illustrate the scale – both the Paris agglomeration and Bavaria individually have a higher GDP than Poland alone), it is hardly surprising that voices have reemerged in the public debate claiming that France and Germany dominate the European Union[10]. Examples are aplenty. It is symptomatic that of the EUR 672 billion[11] of public aid approved by the European Commission after the introduction of new rules in response to Russia’s full-scale military aggression against Ukraine, nearly 80% was allocated to French and German companies[12]. Germany has often ignored common EU provisions without major consequences (for instance when purchasing COVID-19 vaccines[13]) and has successfully managed to protect its own business against measures that curb its privileged position. For example, Deutsche Post has maintained a pricing policy that violates rules of competition within the EU since at least 2001[14].

- Key directions of proposed amendments to treaties

The approximately one hundred and twenty pages-long document adopted by the European Parliament Committee contains a number of proposals of amendments to key provisions of the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union – regarding both the division of competences between the EU and individual member states, as well as to some specific EU procedures, or the degree of harmonisation of regulations, e.g. taxation, between member states.

The relevant document is divided into two parts: the resolution itself, relatively short, containing a justification for the proposed amendments and their general description, and an extensive annexe containing specific proposals for amendments to the treaties. Before scrutinising these amendments and grouping them into broader blocks, it is worth having a closer look at the first part of the resolution. It almost perfectly corresponds to the discourse on the directions of evolution of the European Union outlined in previous paragraphs: changing the treaties is at least advisable, if not necessary, due to, among others, “unprecedented challenges and multiple crises”, and should result in “increasing the Union’s capacity to act” and “enabling the Union to address geopolitical challenges more effectively”. It is clear that this is an exact continuation of narratives described in the first section of this memorandum – the Union is no longer to be a platform for the coordination of policies and economic cooperation between European countries, but in fact a separate political entity.

Importantly, it is to be constructed differently than thus far, because the adopted document contains a number of changes in the structure of the Union itself. Sometimes they are limited to pure semantics, for example, the European Commission is to become the Executive Body; but in some cases, they are of a deeper nature, while in others they appear quite obscure. The text includes, for example, a previously unknown institution of the President of the European Union. It would seem that this is a meaningful change, because for the first time an individual presidency would concern the Union as such, and not one of its bodies. The logic behind the proposed changes suggests that in practice the President of the EU would replace the President of the Commission (in the updated version – the Executive Body). The description of the procedure for electing the President of the EU was replaced in the document by the description of the procedure for the President of the Commission. At the same time, however, the chairperson of the Executive Body is mentioned elsewhere, whose election procedure remains undescribed. It is difficult to draw conclusions from this structure regarding the real intentions of the authors – either the EU President is in fact simply the chairman of the Executive Body, and the inconsistency in the nomenclature is a clerical error, or the blankness of this office’s (the EU President’s) description is an intended effect. In any case, it is noteworthy that in the new structure, the EU President is to independently present the composition of the Executive Body, which would then have to be approved by the European Parliament. Until now, the composition of the European Commission was selected by the European Council, including suggestions made by member states. Therefore, the new model for selecting the composition of the Commission does not take into account any role of the member states. Furthermore, not all member states would be represented at the level of the Commission – the proposed regulations introduce a maximum number of fifteen Commissioners.

The procedure for electing the EU President (and/or the Executive Body) is also interesting. Until now, the candidate for the President of the European Commission was presented by the European Council (heads of individual member states) and approved by the European Parliament. In the amendment, the order is reversed: the candidate is selected by the Parliament and approved by the European Council. Thus, the actual decision-making burden is transferred from the level of representatives of nation states to the level of Parliament. Similarly, the decision on the composition of the European Parliament, which was previously made by the European Council (unanimously), would, because of the changes, be made by the EP itself by a simple majority of votes. In other words, while until now the division of the number of seats held by individual member states had to be the subject of an agreement between the heads of all countries, according to the proposed solution it would be made by the Parliament itself by a simple majority. Even if the general rules of degressive proportionality and the minimum and maximum number of seats are maintained, this solution creates room for changing the national composition of the EP.

In the above-mentioned scope, there is an obvious shift of competences from the European Council, formed directly by representatives of the member states, to the European Parliament and the President of the EU. This is one of the manifestations of the spirit of centralisation and separation of the decision-making process from representatives of individual countries, manifested in many places in the discussed document. Changes regarding the European Parliament are additionally important in that, according to the proposals presented, it would be equipped with a direct right of legislative initiative, as well as the right to submit to the European Council a request to convene a European referendum, which is another novelty, although described rather generally in the resolution. Changes in the scope of the possibility of using emergency measures by EU bodies can be read in a similar spirit. The procedure described in Art. 122 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU currently provides that the Council:

- on a proposal from the Commission, may decide, in a spirit of solidarity between Member States, upon the measures appropriate to the economic situation;

- where a Member State is in difficulties or is seriously threatened with severe difficulties caused by natural disasters or exceptional occurrences beyond its control, on a proposal from the Commission, may grant, under certain conditions, Union financial assistance to the Member State concerned.

New article 222 section -1 provides for a completely different procedure: “In the event of an emergency affecting the European Union or one or more Member States”, the EP (by a simple majority) and the Council (by a qualified majority) would be able to grant the Executive Body “extraordinary powers, including those to enable it to mobilise all necessary instruments”. The obscure nature of this procedure is extremely worrying.

Structurally, attention should also be paid to changes in the European Commission/Executive Body enabling the appointment of undersecretaries who would be assigned specific portfolios or specific tasks. This creates room for further strengthening of the staff of the Executive Body. At the same time, the question arises about the (at least superficial) rationality of this proposal, if we take into account the fact that Directors General already play or could in fact play an analogous role. The document adopted by the committee also proposes expanding the composition of the Executive Body to include the Union Secretary for Economic Governance. This is a manifestation of another tendency visible in the text, i.e. the desire to expand the catalogue of EU competences in the field of universally understood economy.

In the above context, attention should be paid to several of the most important proposed changes. AFCO recommends, primarily, a far-reaching extension of the possibilities of harmonising tax regulations and rates within the Union, by amending Art. 113 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. As it currently stands, harmonisation of tax legislation requires unanimity of the EU Council, applies only to indirect taxes (including turnover and excise duties), and is limited only to cases where such harmonisation is necessary to ensure the establishment and functioning of the internal market and to avoid disruptions of competition. The possibilities of establishing common tax regulations are therefore strictly limited under the current regime. The presented proposal substantially modifies this regime, making harmonisation also possible in relation to direct taxes (such as income taxes) – it would not have to be necessary to become possible, and (most importantly) it would not require the consensus among all member states, because it would be decided on by means of an ordinary legislative procedure.

This last part is probably the most frequently elaborated on aspect of the proposed amendments. In many key areas, including not only the above-mentioned tax harmonisation, but also some provisions related to compliance with the rule of law, as well as defence and external policies of the EU, the presented document assumes a departure from the principle of unanimity in favour of majority voting. Changes to the formula for determining simple and qualified majority are also proposed – their broader description requires additional context and can be found later in the document.

The specific emphasis placed on the new proposals on issues related to labour law and social policies is also noteworthy. It is proposed, among others, that the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU should explicitly refer to the European Pillar of Social Rights (EPSR) in the case of certain provisions. Thus far, it has been a relatively soft (as in non-committal) document with no direct effects, containing a general description of the recommended directions of social development. Even though it was referred to during works on, among others, amendments to the regulations on the posting of workers or common rules for determining the minimum remuneration for work, in principle it remained a general declaration instead of a binding legal act. Meanwhile, the new wording of the TFEU provides that the guidelines of the EU Council regarding employment policies, which are currently being formulated, are intended to ensure the implementation of the principles and rights contained in the EPSR. This is a new element that makes the implementation of the provisions of the Pillar a kind of obligation arising from the treaty, which goes hand in hand with appeals of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D), among others, thus making the issue of social rights one of EU’s priorities and the implementation of the principles of the Pillar subject to ongoing control and monitoring[15]. The described change is crucial, because the assumptions of the Pillar are relatively far-reaching and include, among others: provisions regarding social protection for self-employed persons, recommendations on shaping the level of wages in the economy, or even a reference to the concept of a minimum guaranteed income[16].

The resolution also includes important provisions in the field of climate policies – both in the context of EU competences and their rank on the European agenda. As a result of the proposed changes, protecting the environment and biodiversity, as well as making commitments as part of global negotiations on climate change, would become one of the so-called exclusive competences of the EU. This means that member states could undertake any activities in this field only within the framework of the delegation of powers granted to them by official bodies of the EU. Furthermore, the EU’s energy policy is to be, by treaty, aimed at designing the entire energy system in line with international agreements on mitigating climate change. Again, this means a commitment to pursue specific goals arising from international climate agreements. The common trade policy is also to be consistent with the goal of climate neutrality.

The changes proposed in the context of the European investment landscape are interesting too. According to the resolution, member states would be obliged, for example, to ensure the implementation of investments necessary to achieve European economic, social, environmental, and security goals. A permanent mechanism for monitoring and examining foreign direct investments (FDIs) in the EU is also to be established, which could be used to protect European interests. The resolution does not elaborate on the details of the functioning of such a mechanism, but in the context of its overall goals, it is difficult to avoid the impression that it could be an instrument used for decoupling purposes – not only in relations with China which tend to raise ethical doubts from time to time. In the wording of the treaty proposals, the desire to make Europe independent also from the US is clearly visible. In this context, one can interpret them as demands for the creation of a Defence Union with permanently stationed joint units under European command, an arms purchase system using the European Defence Agency, as well as the principle of mutual aid. One of the resolution’s rapporteurs, Helmut Scholz (incidentally, a graduate of MGIMO – the Moscow State Institute of International Relations), explicitly stated in his position that changing the treaty would have to be accompanied by steps towards independence from NATO.

- Consequences of the proposed changes for Poland

The possible implementation of the described amendments to the treaties would have far-reaching consequences. These are obvious for the European Union, and potentially dangerous for Poland.

Increasing the scope of EU competences in the field of economy and setting a course for a harmonisation of direct taxes placed in the context of, among others, implementation of the EPSR should be considered primarily in terms of their impact on Poland’s competitiveness.

The sole rational objective of harmonising direct taxes – and potentially also social security systems and wage regulations – within the EU is to limit cost competition within the community. Already in 2005, France and Germany called for the harmonisation of corporate income tax, at least in a selected group of countries, for example members of the eurozone, for fear of “tax dumping”[17]. The current proposal goes further and applies to all direct taxes, but the arguments may remain the same.

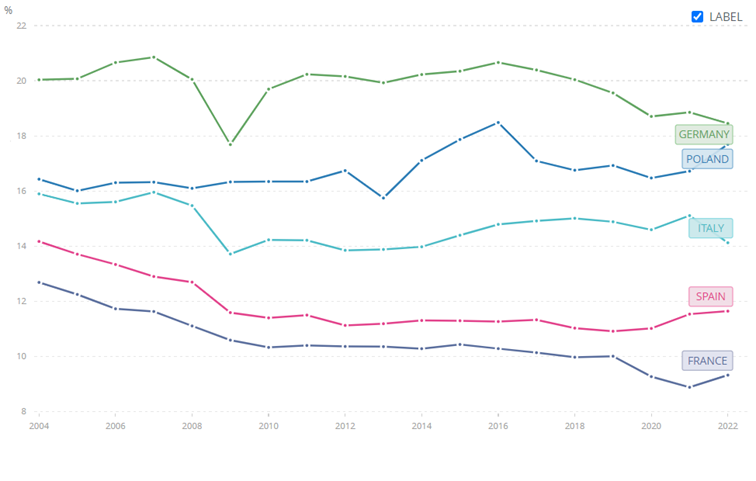

Meanwhile, Poland has recently built an attractive system for taxpayers – at least terms of rates and the real burdens because the regulations remain one of the most complicated and unfriendly in Europe. The basic 12% PIT rate, income tax exemption for young people, an increase in the tax-free amount, as well as the indexation of the second tax threshold while maintaining the 32% rate – all these are solutions that make working in Poland more profitable (meaning there is lower taxation on work) than in Western European countries such as Germany (progressive tax scale 14-45%), Belgium (25-50%), Austria (20-55%), or Spain (19-47%)[18]. Already in 2021, before the changes described above were introduced, PIT revenues as a percentage of GDP in Poland were higher than in some countries in CEE, but significantly lower than in the wealthy countries of the “Old EU” as illustrated by the chart below.

[19]

In 2022, the share of PIT in GDP decreased in Poland by one percentage point to the level of approximately 4.4%[20]. This would mean that we are 5-6 percentage points away from the countries that collect the most income taxes from their citizens, and this value should be understood as the maximum ceiling for the potential convergence of PIT burdens, which in such an extreme scenario would involve the need to more than double the income tax burden.

The same applies to corporate income tax. The 9% rate introduced in Poland for small taxpayers, the so-called Estonian CIT, or a number of other reliefs in the form of measures stimulating investments are solutions that can be evaluated in various ways, but in practice they boil down to the fact that the amount of charges imposed on legal entities in Poland also remains highly competitive. The basic 19% CIT rate remains one of the lowest in Europe[21]. This obviously translates into Poland’s attractiveness for foreign investors – according to some rankings, we are in the top three best destinations for FDIs[22]. According to hard data, Poland in 2022 was ranked among the top ten EU countries with the highest number of foreign investment projects, recording a remarkably high 23% increase in this respect[23].

It is also worth pointing out that partial harmonisation of, for instance, the corporate income tax is already taking place through the directive implementing the second pillar of the OECD agreement on domestic tax base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS), which is only an additional argument in favour of the thesis that, apart from the current process initiated by AFCO, one should expect not only regular returns of harmonisation concepts within the economy, but also their enforcement by various methods that do not require changes to treaties.

One should also remember that arguments regarding an alleged “social dumping”[24] were in the past made use of in initiatives affecting Polish businesses – the best example of which is the dispute over the posting of workers, during which representatives of countries with high labour costs (and therefore, above all, wealthier “Old EU”) accused countries with lower labour costs (including Poland) of spoiling local labour markets and unfair competition by pushing forward the concept of “the same pay for the same work at the same place”[25]. There is a malicious theory according to which, together with the so-called mobility package, these regulations were aimed at inhibiting the importance of the Polish transport industry, which is still essential for intra-EU trade[26]. Introducing the assumptions of the European Pillar of Social Rights in the treaties would create an ideal space for a continuation of this type of practices. This, in turn, would generate further threats of loss of competitiveness for drivers of Polish economic growth. Two examples that ought to be mentioned in this context are business services and industry.

According to a report by Deloitte, Poland is the second most preferred place to locate shared services centres globally[27] and outclasses the whole of Europe in this respect (only Portugal and Spain are in the top ten). The key factor in this respect is, of course, cost reduction, which in turn is directly reflected in the employment costs in a specific country. Surely, it also helps that Polish workers are highly qualified and valued around the world. Meanwhile, the sector generates less than 4.5% of Poland’s GDP and employs half a million people[28], developing in recent years with exceptional dynamics.

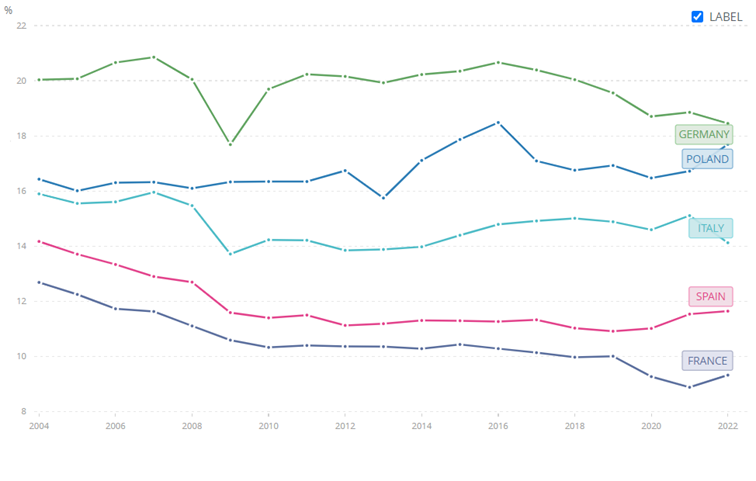

As for industry, contrary to the European trend of deindustrialisation, the share of production in GDP in Poland remains relatively high. In 2004, Poland on par with Italy in this respect, significantly lagging behind Germany. As of today, we have reached the level of our western neighbour, significantly overtaking the Italians. At the same time, such economies as Spain and France have consistently been recording declines in the share of manufacturing in GDP. The chart below illustrates this trend since 2004[29].

[29]

In nominal values, the volume of Polish industrial production obviously lags significantly behind the analogous indicators for the above-mentioned economies. However, should we maintain our dynamics over the next two or three decades, we might have a substantial chance to become one of the European industrial leaders (although Germany would remain out of reach). Looking at the conversion rate per capita, this may happen even sooner. The increase in costs induced by the harmonisation of social security and taxes would clearly have a negative impact on this process.

Similar reservations should be made with regard to the provisions concerning climate policy and the energy market. Poland, to a higher or lower degree accepting the direction of the EU energy transformation, is fighting to have its specificity taken into account. Or rather: the specificity of its initial state, in which the economy inherited from the Polish People’s Republic was based on inefficient heavy industry that made use of energy from fossil fuels only – hard coal in particular. Suffice to say that 98% of electricity in Poland in 1990 was generated from coal combustion[30], while it was slightly less than 40% in the EU on average[31]. However, the Polish mix is consistently changing – today 21% of electricity in Poland comes from renewable energy sources (RES), and less than 70% from coal[32]. Therefore, it would be a false claim that Poland remains passive in the face of climate challenges. At the same time, further “tightening the screws” in the field of EU climate policy (and this is the direction in which the provisions included in the proposal to amend the treaties are heading), without taking into account the fact that over the last three decades we have had to build any an alternative to an energy sector based almost 100% on coal is, of course, against our national interest.

In terms of the economy, the proposed directions of amendments to the treaties are dangerous for Poland. It is therefore worth opposing both current and potential future proposals for harmonisation in tax and social areas, as well as even stricter enforcement of the assumptions of the EU’s climate and energy policies.

In a political sense, the elimination of the principle of unanimity in favour of a majority vote obviously limits the importance of Poland. From the point of view of countries outside the decision-making core of the Union that has the initiative (and Poland is such a country regardless of its size), the need to reach a compromise acceptable to all at the level of the EU Council and the European Council significantly determines the empowered position within the community. Of course, voting is an element of political bargaining, and this is completely normal. The ability to block certain decisions is one of the key assets for countries such as Poland, allowing them to enter the logic of quid pro quo and obtain specific benefits in return for supporting a certain cause. Depriving smaller countries (it is difficult to write about Poland in this context, as it is one of the most populous EU countries, but in any case Poland is among the countries with at most a limited influence on decisions made in Brussels and Strasbourg) of this asset means in practice depriving them of their trump cards – even if the new majority formula in a theoretical sense may weaken France and Germany, although this is not yet clear. While currently it is practically impossible to gather a qualified majority in the Council without the support of France and Germany (these countries constitute less than 34% of the EU’s population, co-opting at least two additional countries necessary to achieve a blocking minority is not only relatively easy, but essentially also guarantees that the threshold of the population represented by decision-making states required to obtain a qualified majority will not be reached), in the proposed model at the mathematical level the situation would be completely different due to the reduction of the required population percentage threshold to 50%. However, raw numbers are not enough to accurately assess the situation. The ability to build coalitions remains key in any system. Loose networks of likeminded countries functioning in parallel to official EU structures are becoming more and more important[33], and it so happens that of all the associated countries, France and Germany have the strongest coalition-building skills, which can be grouped into two key sets: the “Founding Six” together with Italy, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Belgium, and the “Big Six”, or G6, together with Italy, Spain, Poland and, until recently, Great Britain. Or nowadays rather the “Big Five” in a post-Brexit Europe[34]. Changes in determining the majority may therefore be a fig leaf covering the actual deprivation of countries outside the very centre of the EU of the initiative and major influence on the decisions made. Of course, it is not the case – and we cannot ignore this – that France and Germany speak with one voice on every issue. On the contrary, there are differences of opinion in this coalition, for example regarding nuclear energy. Ultimately, the duumvirate is also not an optimal solution and, inevitably, at the end of the path there is the centuries old Franco-German dispute on hegemony in Europe. However, in the longer term, the maturity of these political systems and the consolidation of their elites in European structures mean that various current interferences are unable to affect the implementation of the common interest.

All the above arguments do not automatically mean that any interference in the wording of the treaties is against the Polish interest. First of all, some changes – including structural ones – may actually be justified in the context of potential accession of Ukraine, which would be, depending on the scale of the war-related exodus, a country in terms of population equal to Poland or even “weighing more”. Secondly, there are challenges whose nature means that they can only be effectively answered through a community response. Examples of such challenges include migration crises, which may become more frequent or more intense in the coming decades (fleeing the “global south” caused by climate change or economic factors, as well as political instability and wars). Shared external borders require a common approach established, however, by consensus and agreement of all member states. Thirdly and finally, not all of the Union’s components, even those that are absolutely fundamental, function perfectly. One should mention in this place for instance the free movement of goods, services, and labour, as well as equal conditions for mutual participation in the markets of individual countries. In spite of the directions clearly defined in the treaties, a number of countries continue to apply protectionist practices, to the detriment of, among others, Polish companies.

To sum up: the presented proposal of amendments to the treaties is clearly unfavourable for Poland, although fortunately there is an exceedingly small chance of it being pushed through (more on this later). This does not mean that:

- the concepts contained therein will disappear – they will most probably return in subsequent iterations and proposals, perhaps as part of a transaction related to the new enlargement of the EU, perhaps in the form of activities that do not require amendments to the treaties;

- Poland should oppose any modifications to the European Union’s primary law – there are areas that require correction and adjustment to new conditions, but one must remain vigilant of the trap constituting a return to ideas of federalisation with the leading roles of France and Germany remaining unchanged.

- Next steps

Contrary to the sensational tone of some reports, there is an exceptionally long road from the document being adopted by AFCO to the actual amendment of the treaties, and its effective conclusion is virtually improbable. First, the European Parliament must approve the proposal. Then, the EP submits it to the Council of the EU, from which the document is later sent to the European Council. The European Council decides by a simple majority whether to consider the amendments. If such a decision is made, the President of the European Council convenes a meeting of heads of state, delegations of national parliaments, as well as representatives of the European Parliament and the European Commission. The meeting develops recommendations for a conference of representatives of the governments of individual member states. It is this conference that decides by collective agreement to make any changes to the treaties. At the end of the process, the changes must be ratified by all member states.

If the discussed proposal has a future ahead of it, Europe is in for a lengthy process that will take at least several years, and which will also require the consent of each of the member state. The proposals as presented will, in all likelihood, not be adopted. However, as has been mentioned numerous times, the ideas contained in the document will certainly come back, and one must be fully prepared for when that happens.

***

[1] Confer e.g. “The Theory and Reality of the European Coal and Steel Community”, K.J. Alter, D. Steinberg

[2] https://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/EuropeanEconomicCommunity.html

[3] https://www.bruegel.org/blog-post/measuring-political-muscle-european-union-institutions

[4] https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2023-04/HR-Key-Figures-2023-fr_en.pdf

[5] https://wayback.archive-it.org/12090/20230115155855/https://prod-cofe-platform.s3.eu-central-1.amazonaws.com/gi6tv2ypo5kir3dz4jos479obl4a?response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%3D%222022.2472_PL_05.pdf%22%3B%20filename%2A%3DUTF-8%27%272022.2472_PL_05.pdf&response-content-type=application%2Fpdf&X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=AKIA3LJJXGZPDFYVOW5V%2F20230115%2Feu-central-1%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Date=20230115T155842Z&X-Amz-Expires=300&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host&X-Amz-Signature=7b6d71b572d4a326ee6c8d710c997ce662f51170ac389ff64d93d2567191f35b

[6] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2014_2019/plmrep/COMMITTEES/AFCO/PR/2023/10-25/1276737PL.pdf

[7] https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/blob/2617322/4d0e0010ffcd8c0079e21329bbbb3332/230919-rfaa-deu-fra-bericht-data.pdf

[8] https://www.france24.com/en/europe/20230411-president-macron-to-visit-netherlands-amid-row-over-china-comments

[9] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20230505IPR85002/olaf-scholz-we-need-a-geopolitical-larger-reformed-eu-open-to-the-future

[10] Confer e.g. https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/mje/2023/01/02/why-did-the-eu-change-to-a-france-germany-game/

[11] As of January 2023

[12] https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2023/01/17/germany-france-account-for-most-eu-state-aid-heres-why-its-a-concern

[13] https://www.politico.eu/article/germanys-coronavirus-vaccine-side-deal-at-odds-with-legally-binding-eu-pact/

[14] In 2001, the European Commission imposed a fine of EUR 24 million on Deutsche Post for abuse of a dominant position. Three years later, the Commission found German postal regulations to be in breach of intra-EU rules of competence and in abuse of its dominant position. In 2015, the Federal Cartel Office ruled that Deutsche Post was abusing its dominant position. All proceedings concerned, in practice, the use of dumped prices. In October 2023, the German postal market regulator considered forcing Deutsche Post to increase prices.

[15] https://www.socialistsanddemocrats.eu/pl/newsroom/europejski-filar-praw-socjalnych-powinien-byc-tarcza-chroniaca-ludzi-przed-polityka

[16] According to the Pillar: “Everyone lacking sufficient resources has the right to adequate minimum income benefits ensuring a life in dignity at all stages of life (…)”.

[17] https://www.politico.eu/article/france-and-germany-in-plot-to-harmonize-taxation/

[18] Data from: https://taxsummaries.pwc.com/quick-charts/personal-income-tax-pit-rates

[19] Chart generated using the OECD database: https://data.oecd.org/tax/tax-on-personal-income.htm

[20] https://www.gov.pl/attachment/23782ae6-20e1-4955-8b91-a519f9607298

[21] https://taxsummaries.pwc.com/quick-charts/corporate-income-tax-cit-rates

[22] https://www.fdiintelligence.com/content/analysis/the-story-behind-polands-fdi-success-72245

[23] https://www.ey.com/pl_pl/news/2023/05/atrakcyjnosc-inwestycyjna-europy-2023

[24] https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/networks/european-migration-network-emn/emn-asylum-and-migration-glossary/glossary/social-dumping_en

[25] A broader description can be found e.g. here: https://www.mobilelabour.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Bruegel-Social-dumping-and-posted-workers.pdf

[26] https://tlp.org.pl/jaka-jest-prawdziwa-rola-polski-na-europem-rynku-uslug-transportowych/

[27] https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/operations/articles/shared-services-survey.html

[28] https://absl.pl/en/news/p/record-growth-business-services-exports

[29] Chart generated using the World Bank database: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NV.IND.MANF.ZS?end=2022&locations=PL-DE-FR-ES-IT&name_desc=false&start=2004&view= greyhound

[30] https://wysokienapiecie.pl/8002-udzial_wegla_w_produkcji_energii_elektryczna_w_polsce/

[31] https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/figures/share-of-electricity-production-by-4

[32] https://globenergia.pl/ponad-21-energii-pochodzilo-z-oze-miks-energetyczny-i-struktura-produkcji-energii-w-polsce-w-2022-r/

[33] According to experts of the London School of Economics, amongst others: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2019/08/07/how-informal-groupings-of-like-minded-states-are-coming-to-dominate-eu- foreign-policy-governance/

[34] https://ecfr.eu/article/commentary_eu28survey_coalitions_like_mindedness_among_eu_member_states/

See more: 20.11.2023 Memorandum of the Union of Entrepreneurs and Employers on proposals of amendments to European Treaties: A blow to Poland’s competitiveness and while a step towards a European state, the road ahead is still very long

ZPP Newsletter

ZPP Newsletter

Recent Comments