Warsaw, 27 March 2023

Memorandum ZPP – Challenges for the Polish Agricultural Sector

- Despite the negative impact of numerous economic crises in recent years, Polish agricultural enterprises continue to achieve spectacular successes both in the country and abroad.

- However, in the perspective of the coming years, the significant problem for the agro-sector firms operating in the Polish market may be the consequences of the European Green Deal, which may undermine the satisfactory production indicators today.

- For years, agricultural enterprises in the country have been facing a wave of attacks with ideological motives, particularly those functioning in the breeding sector. Numerous problems have recently been taking on the framework of legislative changes implemented at the EU and national levels.

- The development of modern economic and consumer patriotism should now be one of the main strategies for the agricultural sector in the country. Statistics show that Poles attach much less importance to the origin of products than citizens of Western European countries.

- One of the most important tasks for agro-sector firms operating under Polish law should be diversification of the directions of export of agri-food products.

- The recipe for still high fragmentation of domestic farms is to create incentives for joint management within cooperative structures or producer groups. The level of organization of farms in Poland is several times lower than in Western EU countries.

- The last years, starting from the period of the coronavirus pandemic, through the energy price crisis, to the ongoing war in Ukraine, have been characterized by a regular increase in the costs of running agricultural enterprises in Poland. The most significant price increases have been recorded in the areas of fertilizer prices, agricultural fuels, gas, and energy.

Polish agriculture has relatively coped well with the effects of the crisis that has been ongoing for several years. The coronavirus pandemic and its wide spectrum of economic consequences, the breakdown of supply chains, the energy price crisis, which has led to an increase in the prices of plant protection products and fertilizers, as well as the consequences of the war in Ukraine are factors that have nevertheless left their mark on domestic agricultural enterprises.

Polish agro-sector companies felt the effects of all the above-mentioned events, but the diversification of export directions that has been built up for years and the business professionalization of agricultural enterprises allowed them to achieve another record value of food exports from the Vistula River region. In 2022 alone, Polish food producers exported goods worth 26.1 percent more than in 2021, or 47.6 billion euros. Polish products remain competitive in price on international markets. The favorable exchange rate of the zloty against the euro also played a role in the past year’s exports. Domestic suppliers also properly prepared for the consequences of the pandemic and were able to respond to diverse consumer preferences by designing their product offerings appropriately. Surplus production indicators allowed for the full supply of the domestic food market, making agriculture one of the most important pillars of national security, alongside military and energy production.

However, the agricultural sector in Poland still struggles with numerous problems that effectively hinder the stabilization of the functioning of some entities on the one hand and their development on the other.

The European Green Deal

The European Green Deal is an EU economic strategy that places particular emphasis on shaping a communal economy while taking into account restrictive climate goals. In the context of the agricultural sector, the two main components of the Green Deal are the Biodiversity Strategies and From Farm to Fork. These strategies entail changes that will fundamentally impact the development of EU farms and a decisive shift towards ecological farming (based on EU guidelines). According to the European Commission’s assumptions announced in 2020, they include a 50 percent reduction in the use of plant protection products and a 20 percent reduction in the use of fertilizers by 2030, the mandatory allocation of 25 percent of the area for organic production, and a reduction in the number of antibiotics used in animal husbandry.

The European Commission maintains that the new strategy for agriculture will make this sector of the economy more modern and environmentally friendly, and should not result in significant production declines. However, units under the supervision of the Commission have not presented concrete calculations regarding the impact of the planned reforms on agricultural production indicators. Relevant research has been presented by USDA, HFFA Research, the Joint Research Centre (JRC), the University of Cologne, and the Wageningen University and Research Centre scientists. In their view, the new shape of EU agriculture could seriously threaten the EU’s position as a group of countries that are secure in terms of access to food. This is particularly important in light of the war in Ukraine and the uncertain financial situation of many EU farms, which, faced with significant increases in the cost of doing business, may limit production. Experts from the Wageningen University and Research Centre have calculated that EU agricultural production could be reduced by 10-20 percent after the full implementation of the regulations, and up to 30 percent in relation to certain specific crops. Difficulties may also arise in the livestock sector, where scientists point to potential production declines of around 20 percent for beef and about 17 percent for pork production. This will result from the limited use of certain veterinary medicines and the reduction in the production of feed crops (most of the grain grown in Poland is intended for the feed industry).

Representatives of the Polish agricultural sector also point out that some of the EU regulations have a much greater impact on domestic companies than on those in the western part of the Community. Concerns include the mandatory transfer of land for organic production, which, as representatives of the agricultural sector rightly point out, is usually low-yielding. According to data from the Supreme Audit Office, between 2012 and 2019, when the average area of organic crops in the EU increased by 25 percent, it decreased by the same value in Poland. This puts our country in a more difficult starting position compared to Germany, France, and a number of other countries in the western part of the continent.

Similar doubts arise regarding the restriction of the use of plant protection products under the EU directive on the sustainable use of plant protection products (SUD). The European Commission’s requirement concerns a 50 percent reduction in the use of PPPs, based on their current levels of use. In practice, this means that Poland will be a country disadvantaged compared to other Western European countries. In 2022, Poland used 2.1 kg of PPPs/ha, while the EU average was around 3.1 kg/ha, with significantly lower levels of use in countries on the southeastern flank of the Community. For comparison, the average use of PPPs in the Netherlands in 2022 was about 8 kg/ha. After the planned reduction by the European Commission, Poland will be able to use a maximum average of 1.05 kg of plant protection products/ha, while Dutch farmers will be allowed to use 4 kg of PPPs/ha – twice as much as Poland uses today, before the full implementation of the SUD.

According to numerous experts, the planned reduction may lead to the uncontrolled spread of agricultural pests. Restrictions, as emphasized by sector representatives, can effectively prevent the proper protection of crop plants in Poland.

The Union of Entrepreneurs and Employers believes that regulations shaping the EU agricultural economy should be based on solidarity, meaning fair, and favoring a certain group of countries at the expense of others is absolutely unacceptable. The government side should make every effort to ensure that Polish agricultural enterprises are not disadvantaged as a result of the implementation of EU regulations.

Winning against hate

Poland is one of the leaders in food production among the countries of the European Union, particularly in the livestock sector. According to data from the National Center for Agricultural Support, meat, meat products, and livestock accounted for the largest group of goods in national exports (20% of the total value of agricultural and food exports from Poland). In the last year alone, the foreign sales of this category amounted to a value of 9.6 billion euros, representing a year-on-year growth of 37%. Additionally, the dairy production sector exported goods worth over 3.6 billion euros (+37% YoY) in the previous year, which indicates the dynamic development of animal production in the country. Poland is now an EU leader in the poultry market, one of the top egg producers, an important player in the dairy market, a significant supplier of pork and beef, and a world champion in fur animal breeding.

The livestock sector is now a kind of pearl in the crown of Polish agriculture. The high standards that Polish farms operate under, combined with the competitive price of our products, make Polish meat, milk, cheese, and eggs sought-after goods in many regions of the world.

However, it is difficult not to notice that the growing position of domestic producers on foreign markets has made their companies the target of numerous attacks by organizations unfriendly to the animal husbandry sector. Campaigns such as “The End of the Cage Era,” “The End of the Slaughter Era,” “Meat Tax,” “Ban on Fur Animal Farming,” “Elimination of the Possibility of Slaughtering for Religious Communities,” campaigns against popular “3” eggs, and other similar initiatives have effectively absorbed the attention of producers in recent years, significantly hindering their business development. It should be noted, however, that the possible consequence of actions such as the introduction of a ban on the use of cages in the breeding and rearing of poultry, additional taxation of meat products, regulation of meat under the C40 agenda, or the departure from “3” eggs by successive retail chains (based on arguments that have been repeatedly refuted by scientific communities) may translate into a significant reduction in agricultural production indicators in the country. It should also be noted that many campaigns against animal husbandry are inspired by purely ideological motives. However, while we fully respect the decision to give up consuming animal products, we believe that this should always be a choice, not a compulsion.

According to the Union of Entrepreneurs and Employers, every effort should be made to ensure that animal welfare in Poland is at the highest possible level, but any moves in this regard should be made with the utmost caution so as not to undermine the position of domestic firms. Raising production standards is a global trend today, which is scientifically justified. However, revolutionary movements towards the organization of breeding, advocated by activists from some non-governmental organizations, may lead to a situation in which Chinese or MERCOSUR companies, i.e. locations far from the breeding standards prevailing in Europe, replace Polish or broader European producers. The market does not tolerate a vacuum, and sudden restrictions on the production of animal-derived food in Europe will not lead to a long-term decrease in its consumption on a global scale.

Meat consumption in the EU amounted to 69.8 kg per capita in 2020, which was more than twice the global average. Limiting meat production in the EU – as is the case with dairy or eggs – will not result in a decrease in consumption, but will only increase the scale of importing these products to the European Union, limiting the position of European companies and reducing the quality of food.

Building a strong brand “Poland”

The idea of modern consumer patriotism should guide the national agricultural economy. In Poland, numerous campaigns have been carried out for years to awaken consumer patriotism among the citizens. However, the results of these campaigns are far from ideal. Although the share of domestic products in the market is still increasing, the average Pole purchases fewer domestically-produced products than in Western European countries. According to a survey conducted by “Polish Countryside and Agriculture,” only 56% of non-farmer Poles consider the country of origin of a product to be important. It’s not surprising since real actions to raise awareness of what truly constitutes a Polish product and what is just a simulation have only been implemented in the last decade. The majority of Poles still do not know how to differentiate Polish products from those representing foreign capital.

Certifications, galas, campaigns, conferences, or even whole congresses have not fulfilled the expectations placed on them. Neither symbols supposedly indicating the Polish origin of a product nor even a barcode starting with the number 590 provide consumers with certainty that the purchased goods were actually produced by a company representing Polish capital. This does not mean that the domestic market should be closed to products delivered by foreign companies – Poland is not self-sufficient in the food market and does not have such aspirations today. The key issue should be building knowledge that allows consumers to make informed choices between foreign and Polish products.

A modern approach to consumer patriotism requires a focus not only on the consumer aspect but also on institutional support for domestic companies that comply with EU law. Building a strong position for Polish brands both domestically and internationally should become one of the main goals of the Ministry of Agriculture, as well as the Ministry of Development and Technology, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and institutions subordinate to the Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development, with particular emphasis on the National Centre for Agricultural Support.

The agricultural sector in Poland has a wide range of opportunities to enable Polish products to gain a reputation comparable to world-renowned “French cheeses” or “Italian wines”. Consumer and economic patriotism should be nurtured as it ensures proper circulation of capital in the economic cycle. If supported by an appropriate legislative environment, it can be a real driving force of the Polish agricultural economy. This idea is not new – the importance of building a strong “Poland” brand was emphasized by the government as early as 2015, during the announcement of the Plan for Responsible Development.

Diversify exports

For almost a decade, one of the main goals set by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development has been to diversify the export destinations of agri-food products produced in Poland. The importance of expanding markets beyond the country’s borders was highlighted by the coronavirus pandemic and the war in Ukraine, which disrupted supply chains and affected demand for food products in the European Union market.

Poland has been steadily increasing its share of non-EU countries as recipients of domestic products. In 2022, Polish agricultural companies sold goods worth a total of EUR 12.3 billion to non-EU countries. This is 20 percent more than in 2021. Outside the European Union, we mainly sold milk (EUR 1 billion), poultry (EUR 990 million), wheat (EUR 776 million), chocolate and chocolate products (EUR 773 million), bread and bakery products (EUR 731 million), and tobacco products (EUR 612 million).

In 2022, Polish goods were mainly exported to the United Kingdom (EUR 3.7 billion), Ukraine (EUR 945 million), the United States (EUR 770 million), Saudi Arabia (EUR 521 million), Israel (EUR 439 million), Norway (EUR 296 million), and Algeria (EUR 242 million). For each of these countries, there was a significant increase in the value of exports, with the UK seeing a 25 percent increase, Ukraine a 16 percent increase, and the US a 16 percent increase.

It should be emphasized that such significant increases in foreign sales values were largely caused by increases in production costs, which resulted in price increases for products. Nevertheless, the upward trend in foreign trade of agricultural and food products to non-EU countries was already noted before the coronavirus pandemic, and positive trade balances indicate proper planning of the global trade exchange.

However, despite undeniable successes, Polish food exports outside the European Union accounted for only about 26 percent of the total export of agricultural and food products from Poland. One should not deceive themselves that non-EU markets will replace the position of the EU market, but the intensification of trade exchange with three key areas should be demanded: Ukraine, China, and countries in the northern part of Africa. Today, the presence of Polish companies in these regions of the world is mainly the result of entrepreneurs’ efforts. Increasing the state’s involvement in supporting negotiations on trade exchange conditions – in relation to these three groups of countries – is crucial.

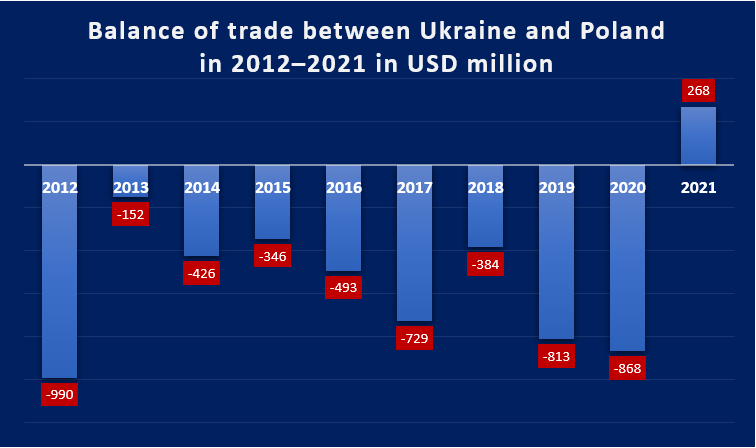

Regarding Ukraine, which is potentially a very important partner for Polish food producers, the trade balance in the last “measurable” period, i.e., in 2021, was unfavorable for Poland. Polish companies exported agricultural and food products worth 811 million EUR to our eastern neighbor while importing food worth over 919 million EUR at the same time. In recent years, the growth dynamics of imports from Ukraine have also been higher than in relation to exports. Only in the period 2020-2021 did the import of goods from Ukraine to Poland increase by 27 percent.

Poland mainly exports milk and dairy products to Ukraine. They accounted for 15% of all agricultural exports to this country. Cheeses, curd cheese, butter, and milk fat also occupy an important place in the export structure. Poles also export significant quantities of yogurt, cream, fruits, confectionery, and animal feed products. However, considering the significantly surplus character of domestic agricultural production, this is still too little. The revival of foreign trade in food products with Ukraine, with particular emphasis on reversing the unfavorable balance of foreign trade, should become one of the main challenges in the export of domestic products. Inevitable production declines in Ukraine caused by the Russian invasion now create an opportunity for Polish exporters who have gained the possibility of establishing themselves in the market of their eastern neighbor. Increasing exports from Poland is also desirable for the Ukrainian side, which must quickly deal with the supply gap caused by massive aggressor attacks on agricultural infrastructure.

The increased role in the export map of the Polish agri-food sector should be played by China, the world’s largest consumer market. The only significant product sent to the Middle Kingdom for years has been dairy products. In 2021, Polish companies from this sector sold products worth about 1.76 billion euros to the Asian hegemon market. However, this is still a drop in the ocean of needs. The export of agri-food products from the largest EU economies to China exceeds today’s Polish indicators many times over. The success of the dairy industry should give other leading sectors in the country food for thought. An increase in exports to China could be realistically achieved, for example, by the poultry industry, which is crucial for the Polish agricultural economy. However, there is a significant need for institutional support, which has so far been ad hoc and often only illusory. Meanwhile, the dynamic development of successive retail chains in China and the thriving online trade make it easier to reach consumers with new product categories every day.

The natural direction for expanding exports should also be Arab countries and Israel. Poland is already strongly present in these markets, but the potential has remained untapped for years. The most desired Polish products there are grains and meat products from halal and kosher slaughter systems. Especially the latter two categories are exceptionally lucrative, and Poland – thanks to competitive prices and high-quality deliveries – can increase its engagement in exporting these products to countries in the region.

Increase in costs

The recent years – starting from the period of the coronavirus pandemic, through the energy price crisis, to the ongoing war in Ukraine – have seen a regular increase in the costs of running agricultural businesses in Poland. One of the most important factors here is the increase in fertilizer prices, which are necessary to maintain high yields and soil quality. Another factor influencing the rise in costs of running agricultural businesses is the increase in gas prices. Gas is used to heat buildings and equipment, but it also constitutes a major component of the final price of fertilizers.

According to data published by the European Statistical Office, in the last year, the costs of agricultural businesses in the European Union countries increased by nearly 40 percent, which is a huge challenge for farmers. At the same time, it was pointed out that agricultural product prices in the EU increased on average by about 30 percent, which does not allow for “catching up” with the high production costs. However, it is worth noting the huge disparities between EU countries. The cost of agricultural production in Lithuania increased by 65 percent in the last year, while in Denmark the increase was only 7 percent.

Eurostat has also analyzed the costs of agricultural production such as the cost of fertilizers and soil improvers, which have increased by an average of 116 percent in the European Union. In addition, energy and fuel costs have increased by 61 percent.

According to Eurostat data, Poland ranked 7th last year in terms of the growth of agricultural production costs in EU countries and 5th in terms of the growth of agricultural product prices. The data indicates the complexity of the situation in the agri-food market in Europe and the need to implement measures to protect the interests of agricultural entrepreneurs.

Immediate institutional financial aid, while in many cases beneficial for food producers, should not be a permanent mechanism. According to the Union of Entrepreneurs and Employers, schemes should be implemented to maximally relieve entrepreneurs by rationally reducing the level of contributions, taxes, and other costs that effectively tie the hands of domestic companies in the agricultural production sector.

Problematic fragmentation of farms

The problematic fragmentation of farms in Poland, resulting from the shaping of the agricultural policy during the communist era, has remained a significant issue for the national agricultural sector. This has a decidedly negative impact on the negotiating power of Polish farmers. The average land ownership per person employed in Polish agriculture, as indicated by Eurostat, is only 8.7 ha/person. Meanwhile, the EU average in this regard is 19.2 ha/person. Poland is also well below the average for the region. For example, in Hungary, the land ownership rate is 11.9 ha/person, in the Czech Republic, it is 33.5 ha/person, and in Slovakia, it is as much as 40.5 ha/person. The average size of a Polish farm in 2022, according to GUS data, was only 11.32 ha, which is not much when considering Eurostat’s 2020 data indicating that the average size of a farm in the EU was 17.4 ha. Poland is particularly behind compared to the largest agricultural economies in the European Union. In France, it is around 45 ha, in the Netherlands just over 22 ha, and in Germany over 53 ha.

An additional advantage of smaller farms in Western Europe is their high rate of the organization into cooperative structures or groups of agricultural producers. This allows small entities to compete on equal terms with the largest companies in the industry. This opens up a path for negotiations with the largest points of sale for goods and significantly increases their ability to conduct exports, which requires the accumulation of significant amounts of homogeneous goods. Achieving this goal is only possible with proper production planning, which is the responsibility of cooperatives or other forms of farmer association.

The organization rate of farms in Poland is around 15%, while in France, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Scandinavian countries, it is over 90%. This means that 85 out of 100 farmers in Poland remain with their problems without real support. The fact that agricultural cooperatives payoff is evidenced by the fact that French cooperatives generate annual revenues of EUR 85 billion, Denmark – EUR 30 billion, and in the Netherlands – EUR 25 billion. In Poland, however, a high percentage of farm organizations is only recorded within the dairy production and fruit growing sectors.

An additional advantage of the special organization of farms in Western European countries, i.e., Agricultural Commodity Exchanges, is their presence at all levels of the agricultural production and food trade chain.

Poland, even before the communist period, laid the foundations for the development of agricultural cooperatives in Europe. However, the times of the People’s Republic of Poland distorted this form of common management, discouraging Polish farms from it for years. Today, the only chance for the development of cooperatives is to create regulatory incentives. In this context, recent changes in the Corporate Income Tax Act should be pointed out, which introduced “tax exemptions for the trade in products for the production of which the cooperative was established” for cooperatives functioning as micro-enterprises. Under these provisions, cooperatives were removed from the group of taxpayers for property tax on “buildings and structures or their parts and land occupied under them that are owned or in perpetual usufruct of the agricultural cooperative or its association conducting activities as a micro-enterprise.” However, Polish law still provides cooperatives with meager benefits compared to the West for joint management.

Summary

Polish agriculture – despite numerous successes achieved both domestically and abroad – still remains an area of untapped potential. Apart from the discussed challenges, the focus will have to be on, for example, freeing Polish farms from direct EU subsidies, a real fight against epidemics of ASF and avian flu, development of water retention, which can protect us from effects of drought, and a number of other pressing issues.

Companies in the domestic agricultural sector, synergistically cooperating with public administration, have all the arguments to continue the process of professionalization of their activities. Every year, new agricultural enterprises emerge from the group of previously small entities in Poland, which quickly begin to become noticed on the domestic or international market. The Association of Entrepreneurs and Employers believes that the group of over 1.3 million farms in the country is a potential source of future success for the national economy. Many agricultural sector companies are already leading the way in the region, building a positive perception of Polish business in markets around the world.

See more: 27.03.2023Memorandum ZPP – Challenges for the Polish Agricultural Sector

ZPP Newsletter

ZPP Newsletter

Recent Comments