Warsaw, 20th September 2021

Position of the Union of Entrepreneurs and Employers on the draft act implementing the system of Extended Producer Responsibility

The draft act amending the act on the management of packaging and packaging waste and certain other acts presented by the Ministry of Climate and Environment contains solutions that give shape to the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) system to be implemented in Poland.

The obligation to implement solutions in the field of EPR, following the adoption of EU directives, aims to achieve specific environmental goals, including these in terms of recycling levels achieved for individual waste fractions. However, to achieve individual goals, it is essential to develop a measured and effective Extended Producer Responsibility scheme.

The Union of Entrepreneurs and Employers observes with concern that the EPR scheme provided for by the Ministry of Climate and Environment will not bring the desired results in terms of achieving environmental goals stemming from the ideas of circular economy or related to the European Green Deal. The sole effect of implementing EPR in the form presented in the draft act will be the increase in the burden on producers (by introducing a packaging tax), and as a result – another increase in prices.

In our view, the presented draft act in its current wording is not suitable for further proceedings. We call for the draft to be rewritten from scratch in the spirit of care for the environment and with the effectiveness of the system in mind; not to supply the public finance sector with additional revenue.

In connection to the above, the Union of Entrepreneurs and Employers shares a number of comments to the current project, as well as proposals for the future, which will allow to design an optimal EPR scheme that meets the goals and needs of all stakeholders. One should also remember that the final beneficiaries of the system must be citizens and the natural environment.

I. Para-tax character of the proposed EPR scheme

Under the government’s proposal for the EPR system, entrepreneurs producing packaged goods (producers/manufactures) are to be reduced to the role of passive payers who have no real influence on the shape and efficiency of the system. However, this will not entail relieving entrepreneurs of responsibility for the system’s efficiency. A complete separation of responsibility for the result from the possibility of influencing the way the system works is obviously not in line with the basic assumptions of the Waste Directive.

The draft act does not even guarantee the correct application of the net cost principle, i.e. the solution provided for in the Directive (Art. 8a sec. 4 (a), first indent) that would allow the inclusion of the revenues obtained from the sale of the raw material collected by the system in introductory fees. It is an important mechanism that allows for fair settlement of costs incurred by entrepreneurs.

The above framework means that the designed EPR scheme has a para-tax character. Entrepreneurs will be charged with another public levy, which – as the legislator admitted in the explanatory memorandum – will be passed on to consumers.

Apart from the reservations to the cost and organisational effectiveness of the implemented solution, it is necessary to point out a factor important from the consumers’ point of view, which is the increase in the prices of packaged goods. Already now, Poland is one of the European leaders in terms of inflation. The introduction of EPR in the proposed shape will lead to an increase in prices of basic necessities such as food, hygiene products and cleaning products to name a few.

In the opinion of the Union of Entrepreneurs and Employers, in order to implement an optimal EPR scheme, it is necessary to take into account the demands of producers who have declared their willingness to actually participate in the waste management system, thus having a real impact on activities increasing the volume and quality of collected waste. We believe that the EPR system should maximise the synergy between the actions of individual system participants, therefore producers should be allowed to become really involved in the system’s operations.

II. Producers’ responsibility for insufficient recycling levels

To begin with, it should be noted that the draft act is imprecise and does not specifically name the party to be responsible for recycling packaging waste from households.

Importantly, as has been mentioned earlier, regardless of which group of entities will actually recycle waste, in the event of failure to achieve the assumed levels – producers will be financially liable and will have to incur a product fee. This leads to an irrational situation in which entrepreneurs, without any organisational responsibility for the recycling process – will be held accountable for results beyond their control.

In the scheme being implemented, producers are required to pay a packaging fee, and the revenues from this fee ensure the efficient functioning of the EPR system as well as the achievement of specific recycling levels. The product fee will be a punishment against entrepreneurs for ineffective activities of municipalities in the field of waste management. We believe that the responsibility of producers for achieving recycling rates, formulated in this way, is unacceptable.

It is worth emphasising that the constraint to pay the product fee by entrepreneurs is highly probable due to the fact that the draft act does not provide for any tools aimed at increasing the volume and quality of packaging waste collected by municipalities. For this reason, and also due to the lack of financial liability of municipalities for failing to achieve recycling rates, local governments may not be sufficiently motivated to organise efficient waste management systems. In practice, situations may take place where the financial costs borne by the introductory entities (including the packaging fee and the product fee) exceed the costs of packaging waste management, which in itself is contrary to the Waste Framework Directive.

III. Division of packaging waste streams

The draft act divides packaging waste into two streams: waste from packaging intended for households and waste from other packaging (including that generated by trade or services and industrial). This distinction is important, because it determines the obligations (in the field of packaging waste management of this type) of the entity introducing products in packaging intended for households, primarily in the scope of paying the packaging fee in the case of independent fulfilment of these obligations.

In the proposed act, packaging intended for households is defined as the packaging in which a product is placed on the market for use in households and other places where similar products in packaging are used. It seems that the proposed definition is so general that it makes it impossible to clearly determine how to define and distinguish packaging intended for households from others, coming from trade, distribution or industry.

We assume that the authors of the draft act decided to introduce such a distinction from specific recitals of the directive, because the proposed solution is not required by Art. 8a of the Framework Directive and thus constitutes an over-regulation on the part of the Polish Ministry. However, it should be noted that neither the explanatory memorandum to the draft nor the Regulatory Impact Assessment indicate how the above-mentioned distinction of waste streams would contribute to a better functioning of the EPR system.

The Union of Entrepreneurs and Employers fails to see sufficient reasons as to why the introduction of such a solution would be justified. In our view, leaving this provision in its current wording may lead to significant interpretation uncertainty, in particular with regard to introducing products in packaging that can be used by households, trade, services or industry alike.

Furthermore, the separation of waste streams may adversely affect the situation of entities introducing small amounts of products, mostly small and medium-sized enterprises. This, however, is in contradiction with Art. 8a sec. 1(d) of the Framework Directive, therefore we call for the removal of the separation of waste streams from the draft act.

IV. Allocation of the revenues from the packaging fee

The provisions regulating the allocation of revenue from the packaging fee also indicate the para-tax nature of the proposed EPR scheme. According to the contents of the draft act, as much as 80% of the proceeds from the packaging fee will be transferred to communes or associations of communes. However, according to Art. 3 sec. 4 point 12 of the project, local governments will be able to allocate the funds received to cover the costs of receiving, transport and collection of municipal waste referred to in Art. 1. 6r sec. 2 point 1 of the Act on maintaining cleanliness and order in municipalities of 13th September 1996.

The provision formulated in this fashion means that communes and associations of communes will be able to allocate the funds received not only to the management of packaging waste covered by the EPR system, but also to the management of all other municipal waste. Moreover, the draft act does not provide for any tools allowing for reporting of costs. Thus, post-factum determining what part of the funds was spent on the actual management of packaging waste covered by the EPR system may be very difficult in practice.

In the opinion of the Union of Entrepreneurs and Employers, the proposed regulation ought to introduce a restriction according to which local governments may allocate funds obtained from the packaging fee to the management of waste covered by the EPR system only. It feels unjustified to lead to a situation in which entrepreneurs finance the entire waste management system, including municipal waste. The lack of a link between the expenditure of funds obtained from the packaging fee and the real costs of packaging waste management absolutely violates Art. 8a sec. 4(a) of the Framework Directive.

V. Distribution of funds from the packaging fee between communes

As indicated in chapter IV of this document, the presented EPR scheme seems to be an extremely beneficial solution for municipalities (and their associations), as the revenues from the packaging fee will be a significant financial relief for local government finances.

In practice, however, it may turn out that some communes – at the expense of others – will receive funds disproportionate to their waste management needs. The above may occur due to unclear criteria for the allocation of funds obtained from the packaging fee.

The funds from the packaging fee are to be distributed among communes based on two criteria: the share of municipal waste prepared to be reused or recycled and the population index. These criteria will have different weights: 60% and 40% respectively.

It should also be noted that the criterion for municipal waste prepared for reuse and recycling has not been limited to packaging waste. Moreover, the indicator regarding the number of inhabitants is not sufficiently precise, as it does not indicate a specific source from which such data can be obtained or updated in subsequent years.

Designed this way, the system of dividing the packaging fee does not guarantee that communes will receive adequate funds for the execution of tasks related to waste management. The disbursement of funds is to be made on the basis of said criteria, but it is not known how the result obtained after calculating these indicators is to be used for the disbursement of the funds. Basing on the proposed regulations, it will therefore be possible to arbitrarily allocate funds to communes, also in an amount that does not correspond to the actual costs of providing services in the field of packaging waste management, which raises considerable reservations on the part of both communes and producers.

VI. Definition of packaged products’ introducer

The draft act introduces changes to the definition of “party placing packaged products on the market” by specifying the conditions for recognising retail enterprises introducing products in packaging. Such explanation is, however, insufficient and does not eliminate the uncertainty arising from the application of the amended provisions.

The act should also take into account different business models adopted by entrepreneurs, in which the producer is distinguished from the entity dealing with distribution. This applies, among others, to a wide range of companies operating in logistics, transport and e-commerce – all of which are developing sectors in Poland. Under the current regulations, qualifying the liability of a given entity is very difficult, as the definitions of the entity introducing products in packaging and placing them on the market are broad in scope, which prevents an unequivocal determination of the liability of a given entity.

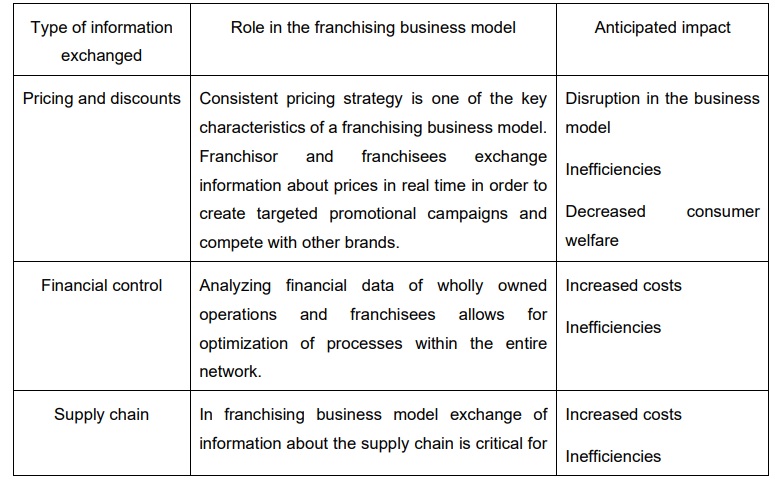

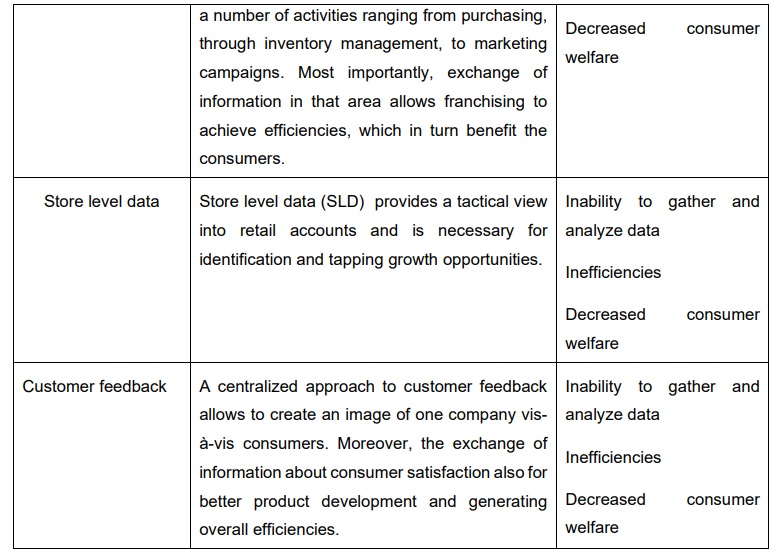

Moreover, in our view, the proposed amendment ignores an important aspect of the functioning of entrepreneurs with regard to franchises implementing systemic solutions in line with circular or other pro-ecological initiatives. Groups of entrepreneurs associated in such networks, operating under the leadership and with the leading role of licensors (franchise operators), since they function within one economic organism which is similar to a corporation, should be able to jointly meet the criteria set out by the act in relation to obtaining the required levels of waste recycling, the content of recycled materials, possibility of separate collection and keeping a common system of records.

VII. Fee collection for processed waste in a circular economy

The definition of packaging intended for households does not distinguish between waste going to the enterprise’s circular economy management system that is to be recycled. While the intention of the legislator to impose a packaging fee on those placing products in packaging on the market in connection with the introduction of waste to municipal waste management systems is understandable, charging this fee for waste processed under the circular economy, which is a system much more efficient than municipal systems, is unjustified and contradictory with the directions of development established, for example, by Roadmap for transformation towards a circular economy, a resolution of the Council of Ministers of the Republic of Poland of 10th September 2019, which assumes the implementation of a support system for enterprises whose business models operate in line with circular economy.

In relation to the above, Art. 18a of the draft act should be modified so that the method of calculating the due packaging fee takes into account the volume of waste recovered by the entity introducing products in packaging and recycled under circular economy, the volume of which should reduce the volume per which the fee is due.

VIII. Determining minimum remuneration for producer responsibility organisations in the form of a notice

Pursuant to the contents of the draft act, the remuneration that is due to producer responsibility organisations (PROs) for the execution of introductory obligations is to be specified in an agreement concluded between the PRO and the introducing party. The rates of remuneration resulting from the concluded contracts may not, however, be lower than the rates established by the minister responsible for climate and announced in the Public Information Bulletin. As is clear from the explanatory memorandum to the draft act: the minister will announce the minimum rates of remuneration in the form of a notice.

We must emphasise that announcing the minimum amount of remuneration for PROs in the form of a notice will constitute a violation of Art. 87 sec. 1 of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland. This provision contains a closed catalogue of sources of universally binding law, without mentioning a notice as a universally binding source of law. Therefore, the notice may not introduce norms of a general or abstract nature that would regulate the legal situation of an indefinite number of addressees.

Furthermore, the draft act does not indicate any range of amounts to be applied when establishing the minimum rates of remuneration. There is also no indication at all of any algorithm that the minister would use when setting these rates.

With this in mind, we ask for the minimum rates referred to above to be regulated at least by way of an ordinance or ministerial regulation, which would constitute an appendix to the proposed act. On the other hand, the act should contain (apart from the delegation to issue a regulation) a range of amounts or an algorithm that would be used to determine the minimum rates. It should be noted that it is impossible to comprehensively analyse the implemented EPR scheme without such important data as remuneration, which affects the costs of producers’ operations.

IX. Exclusion from the definition of hazardous substances

Art. 8 point 14(b) in the draft act is an important regulation, which is, however, limited to only one group of products. This provision excludes detergents from the definition of hazardous substances, and only them. At the same time, this exclusion does not cover a number of consumer packaging for non-detergents, such as air fresheners, repellents, disinfectants etc., which, when empty, do not pose a threat to the environment. We draw your attention to the fact that the composition of this type of products does not include substances classified as toxic or carcinogenic. Empty packaging ends up in the appropriate municipal waste streams, and the tiny leftover amounts of their contents do not have a more significant impact on the environment than the leftovers of other product categories. Moreover, it seems that the creation of an additional category of hazardous substances in relation to packaging waste is unjustified. The methods of dealing with waste which, due to its properties, create various types of hazards are described in separate regulations.

X. Problems with the application of the Act resulting from the adopted vacatio legis

Due to the construction of the draft act, the regulations it introduces are impossible to implement. The act is to enter into force on 1st January 2023, so the first packaging fee is to be paid by entrepreneurs introducing products in packaging intended for households by 15th February 2023. However, the rates of this fee must first be determined by a regulation that may not be issued on the basis of an act that has not yet entered into force, that is prior to 1st January 2023. Furthermore, the issuance of such a regulation requires a positive opinion of the council advising the minister competent for climate matters. This council also cannot be appointed before 1st January 2023, that is before the act enters into force. This construction of the draft act means that: either the minister will issue a regulation on the rates of the packaging fee on the basis of an act that is not yet in force or will issue it without consulting the council, or entrepreneurs will not pay the first packaging fee by 15th February 2023 as the regulation will not yet be issued (full legislative path) and the rates will not yet be accepted by the council.

Summary

Taking into account the commentary collected above, we believe that the draft act in the presented form is not entirely suitable for further proceedings. The prepared amendment contains numerous fallacies of a structural and systemic nature. As a result, the implementation of the EPR scheme in the shape proposed will not only fail to contribute to the achievement of environmental goals, but will also increase the costs of producers’ operations, which will directly translate into increased prices of basic products.

Importantly, the draft is inconsistent with the basic assumptions of the directive. It seems rather difficult to expect a correct implementation of Art. 8a of the Waste Directive. Thus, the enforcement of the act in its present wording will sooner or later result in the necessity to amend it, which will result in even greater legislative chaos and regulatory uncertainty among domestic and international enterprises.

Therefore, it is necessary to ensure that the implemented EPR scheme meets the needs of all stakeholders of the system, which can be achieved thanks to an even distribution of workloads and powers with regard to all stakeholders. It is also necessary to get rid of the para-tax aspects of the implemented system. As of now producers are treated only as payers of a new public levy.

To sum up, the Union of Entrepreneurs and Employers appeals that works are commenced on a new EPR scheme, the framework of which and key solutions included in it will be developed in cooperation with all stakeholders involved in the system to be implemented.

ZPP Newsletter

ZPP Newsletter

Recent Comments