Warsaw, 4 October 2024

Memorandum from the Union of Entrepreneurs and Employers on the proposed composition of the European Commission for 2024-2029

- The European People’s Party (EPP) has filled more than half of the posts within the ‘new’ EC. This heralds a rather moderate direction for public policies.

- As EC chief Ursula von der Leyen has suggested on several occasions in recent months, the main priority of the coming term will be to strengthen the EU’s competitiveness. The way to achieve this goal is through the twin transformations: digital and green.

- Spanish socialist Teresa Ribera was awarded the prestigious portfolio on market concentration and state aid after the ‘iron lady’ Margrethe Vestager.

- In line with the recommendations of the high-profile Draghi report, the EC intends to increase Europe’s competitiveness by placing greater emphasis on new technologies. This will be supported, among other things, by the appointment of a separate commissioner responsible for startups and innovation.

- The appointment of Austrian Magnus Brunner as Commissioner for Home Affairs suggests a tightening of migration policy and raises questions about the future of free movement within the Schengen area.

- The former Permanent Representative of the Republic of Poland to the EU, Piotr Serafin, as Commissioner for the Budget, will be responsible, among other things, for the distribution of funds to the areas most relevant from our perspective, including cohesion policy and agriculture.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen was sworn in for a second term of office on 18 July. Two months later, she proposed the long-awaited composition of the College of Commissioners for 2024-2029. However, before her team assumes their positions, likely on 1 November, the EC chief’s designated colleagues must undergo hearings before the European Parliament. More than one candidate in previous years has fallen at this stage.

Regardless of whether each candidate receives approval from Parliament, the priorities and overall direction of the future Commission, whose actions will impact business, are already known. What does the new composition of the European Commission mean for business and what will Brussels put most emphasis on in the next ‘five years’? Below is a subjective overview of the key findings from the reshuffle in the EU’s main executive body.

- Centre-right still on top

The European People’s Party (EPP), von der Leyen’s parent party, which includes the Civic Platform and the Polish People’s Party, won the European Parliament elections in June, winning 188 of the 720 seats in the chamber. Success was evident both in the allocation of key positions—besides von der Leyen, the Maltese President of the European Parliament, Roberta Metsola, retained her post – and in the distribution of power within the College of Commissioners. More than 50% of the 27 available vacancies have just been filled by the EPP, whose dominance heralds a continuation of the current direction and an evolution rather than a revolution in the creation and development of public policies.

There are many indications that the Christian Democrats will remain in their current alliance with the Socialists and Liberals for the next five years, with both parties having two nominations each for EC deputy heads. At the same time, the designation of Italian Raffaele Fitto as Executive Vice-President for Cohesion and Reforms may suggest a turn to the right. The former minister in Silvio Berlusconi’s government is now a partisan of Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, whose Italian Brothers together with Law and Justice form the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) faction. Its appointment, uncertain in the face of opposition from liberal and left-wing forces, would represent a further step away from the ‘cordon sanitaire’ policy applied to certain groupings of the ‘new European right’. It would, however, make sense in the context of the similar positions of the Christian Democrats and the ECR against parts of the climate regulation, including the Nature Restoration Law, which MEPs from both parties voted against in February.

- Time for competitiveness

As von der Leyen indicated in her programme (so-called ‘political guidelines’) for her second term as head of the EC, her main priority is to strengthen the competitiveness of the European economy, the key to which is to support the green and digital transformation taking place side by side. [5] Among the measures needed in this direction, the politician mentioned the completion of the single market in sectors such as services, energy, defence, finance and electronic communications, or an increase in research funding. She also announced the creation of a Clean Industrial Deal within her first 100 days in office, aimed at increasing the level of decarbonisation-accelerating investment in energy-intensive industries, and proposed ring-fencing the European Competitiveness Fund as part of the Multiannual Financial Framework, the EU’s long-term budget, for 2028-2034. Guaranteeing funding for the development of strategic technologies, including those related to artificial intelligence (AI) and space exploration, can support the emergence of innovation on the Old Continent, consistent with the conclusions of the recent high-profile Draghi report. According to the publication, Europeans are significantly behind the Chinese and Americans in terms of productivity, especially when it comes to the high-tech sector. According to the authors, closing this gap will enable investments of €800 billion per year. A similar steady injection of cash, they argue, will translate into the generation and development of strategic technologies within the community, improving its competitive position vis-à-vis the world’s largest economies.

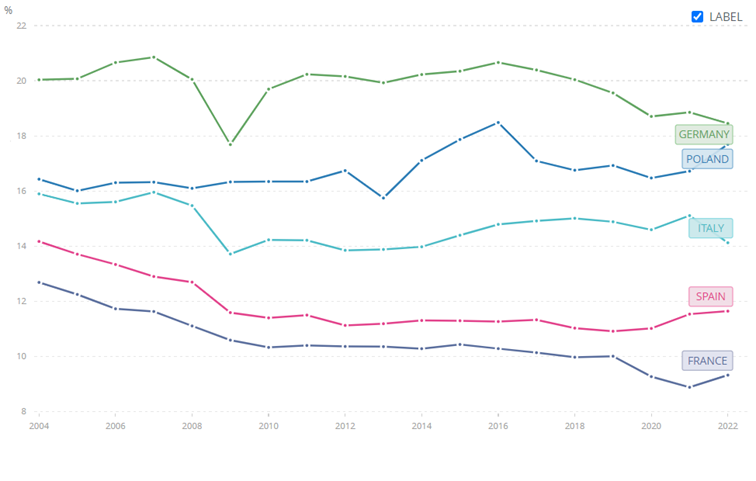

Given the current statistics, appropriate corrective action must be taken immediately. Firstly, the EU’s share of global GDP fell from 21 to 16.5 per cent between 2008 and 2022. At the same time, the US recorded a slight increase, while China, starting from a ceiling of over 8%, matched the European Union. Currently, the economies of Beijing and Washington are growing ten times and five times faster than the EU’s, respectively.

Innovation statistics are equally grim. Today, only 3 of the top 50 technology companies are from the Old Continent, with as many as 30% of Europe’s ‘unicorns’ – startups valued at more than $1 billion – moving their headquarters to the US between 2008 and 2021 due to the greater availability of capital.

The pessimistic outlook is completed by energy prices, in the case of natural gas as much as 4-5 times higher than US prices. This is by no means conducive to the expansion of European business. At the same time, specific doubts can be formulated about the tools to support European competitiveness that are emerging as recommended in the public space – further cash injections or maintaining a course towards a very ambitious green transformation may prove to exacerbate the problem rather than solve it.

- Elevation of a Spanish socialist

Teresa Ribera, the incoming EC Executive Vice-President for a Clean, Just, and Competitive Transition, will play a pivotal role in driving initiatives to boost the EU’s competitiveness. A Spanish socialist and former third deputy prime minister and minister for ecological transition in Pedro Sánchez’s government, Ribera will ensure the EU stays on course to reduce CO2 emissions by 90% by 2040, compared to 1990 levels. This goal will be achieved by greening industry and creating incentives for sustainable investments, a task in which she will be supported by Dutchman Wopke Hoekstra, the future Commissioner for Climate, Net Zero and Clean Growth. Given Ribera’s experience as a former UN negotiator and key architect of the Paris Agreement, she is expected to bring strong principles and determination to the implementation of the European Green Deal.

Notably, the politician will gain oversight of the prestigious Directorate-General for Competition (DG COMP) in addition to her environmental and climate change responsibilities, meaning that, subject to the European Parliament’s approval of her candidacy, she will shape EU competition policy for the next five years. The prestigious portfolio, managed for the past decade by liberal Dane Margrethe Vestager, known for her skirmishes with Big Tech, must today redefine its role, taking into account the impact of the EU’s intensifying rivalry with China and the US and the advancing AI revolution. Therefore, one of her main tasks in her new position will be to review the rules on market concentration and state aid. She is likely to face challenges in finding the right balance between implementing solutions that remove barriers to innovation and support the creation of European champions, while also protecting competition in the internal market from the excessive dominance of the largest national economies, particularly Germany and France. It is these two countries that have the greatest potential to subsidise their companies and thus support their overseas expansion, which could arouse opposition and resentment from the smaller Member States. A significant challenge for Ribera will be to skilfully navigate vested interests while enhancing the competitiveness of European industry and driving its green transformation.

- New technologies as a driver of competitiveness

The appointment of Finnish Christian Democrat Henna Virkkunen as Executive Vice-President for Tech Sovereignty, Security and Democracy should also be seen as a reflection of the new EC’s course on competitiveness. As announced by Ursula von der Leyen in July, one of the pillars of this function will be to foster the proliferation of digital technologies, which is expected to entail a greater ability for Europeans to use them in the development of new services and business models. Achieving this goal is also to be supported by the Apply AI strategy it was commissioned to prepare. In addition, the politician will be tasked with launching the AI Factory initiative providing AI start-ups with access to the computing power of EU supercomputers within her first 100 days in office. The programme is intended to facilitate the training of AI models and has already been criticised for coming onto the EU executive’s radar too late. The most promising AI companies in Europe have long established significant partnerships with US tech giants. For instance, the recent agreement signed in February between the French unicorn Mistral and Microsoft highlights this trend, as noted by the influential POLITICO portal. Importantly for business, on the legislative front, Virkkunen’s responsibilities will be complemented by the presentation of the EU Cloud Act and AI Development proposals, as well as the responsibility for implementing the high-profile Digital Services Act (DSA) and Digital Markets Act (DMA) into national legal orders.

Additionally, it is important to highlight the establishment of the position of Commissioner for Startups, Research, and Innovation within the 2024-2029 Commission. The need for a separate area was first recognised with the appointment of former Bulgarian Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Ekaterina Zakharova, who in her new role will, among other things, manage the billion-euro research and innovation programme Horizon Europe. Her mission, clearly articulated in a public document published by von der Leyen, will also include creating a strategy for European startups and scaleups, expanding the activities of the European Innovation Council (EIC) or drafting the European Innovation Act in a way that increases innovative companies’ access to venture capital and enables them to test their solutions in a supervised environment by generalising the institution of regulatory sandboxes. This wide range of Bulgarian responsibilities sends a clear message about the European Commission’s commitment to positioning Europe in the technological race against the United States and China. However, the announcement of new regulations, the multiplicity of which many believe has prevented the Old Continent from building a global digital business in previous years, may be questionable.

- Fortress Europe is coming

The election of Austrian Finance Minister Magnus Brunner as Commissioner for Migration and Home Affairs seems significant. His country has been successively stiffening its stance towards migration and the free movement of people within the EU for years. While Vienna has indeed been notorious in recent times for actions such as illegally extending temporary border controls, starting to build border walls or blocking the extension of the Schengen area to Romania and Bulgaria, similar initiatives are increasingly becoming part of the mainstream EU debate. Suffice it to say that Germany, too, decided last month to reintroduce controls at all its land borders. Shortly before, Berlin’s representative on the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, had called for the search for “innovative ways” to combat irregular migration. One of these is to be the establishment of extensive partnerships with neighbouring countries, for which the Commissioner for the Mediterranean, Croatian Dubravka Šuica, and the Czech Commissioner for International Partnerships, Jozef Síkela, will be responsible. Their future activities are likely to be inspired, among other things, by the recent agreement between Italy and Albania to return migrants intercepted in Italian territorial waters to special centres in the Balkan country for processing asylum applications. It can be assumed with a high degree of probability that agreements of this kind will become the European Commission-sanctioned norm in the years to come.

- Not just NATO. The Union assumes responsibility for defence.

According to earlier media reports, the EU will live to see its first Defence Commissioner. This is likely to become former Lithuanian Prime Minister Andrius Kubilius, whose portfolio is also expected to include the space sector. As President von der Leyen declared, one of his tasks will be to present a so-called White Paper on the Future of the European Defence Industry within 100 days in office. The document will lay out a strategy for the creation of a European air shield and cyberspace security system and define investment needs to enhance the community’s military capabilities. It also outlines a vision of net contributors’ sceptical perception of joint arms purchases. Although the Commissioner-designate does not underestimate the role of NATO, at the same time he stresses that without the above-mentioned measures, the EU will not be ready for a Russian attack on one of its Member States. [14] In this context, Kubilius calls on European countries to build up minimum stocks of ammunition. This appeal aligns with the nomination of former Estonian Prime Minister Kai Kallas, who is recognized for her aggressive stance toward Moscow, as the EU High Representative for Foreign and Security Policy..

It can be assumed that the future head of EU diplomacy will form a united front with the Lithuanian for the next five years to raise awareness of the threat from the east and actively oppose Russian imperialism. Their alliance on this issue will be all the more important as a change of White House occupant is imminent. A potential victory for Donald Trump could force Europe to be more autonomous on security issues. Then the firm stance of the two representatives of the Baltic republics will become a beacon for the rest of Europe.

In addition, it should be noted that entrusting Kubilius with the mission of drafting a proposal for a space law and formulating a Space Data Management Strategy are in line with the recommendations of Mario Draghi’s report on strengthening the competitiveness of the EU economy by exploiting the potential of innovative sectors, including that of space exploration.

- On the trail of unfair competition from China

In creating her team for the next few years, Ursula von der Leyen decided to pay particular attention to unfair competition from Chinese players, especially e-commerce platforms. Among the responsibilities of veteran European Commissioner Maroš Šefčovič from Slovakia – who will be serving in this capacity for the fourth time – are overseeing trade, economic security, and interinstitutional relations and transparency. Key tasks include ensuring a “balanced economic relationship based on reciprocity” with China, particularly in light of the recent dispute between Brussels and Beijing over Chinese electric cars. Additionally, he will work on finalizing negotiations among member states regarding a customs reform package, as Chinese online retailers currently benefit from a de minimis threshold that exempts goods worth less than €150 from customs duties. He will also be tasked with protecting the single market from an influx of products that do not meet European norms and standards.

The same phenomena will be addressed from a consumer protection perspective by Irishman Michael McGrath, candidate for Commissioner for Democracy, Justice and the Rule of Law. If approved by the European Parliament, he will address, at the request of Ursula von der Leyen, the restoration of a level playing field through the implementation of product safety legislation and the preparation of the Digital Fairness Act.

- Housing needed immediately

Without doubt, one of the most interesting staffing decisions von der Leyen has made is that of appointing Dane Dan Jørgensen as Commissioner for Energy and Housing. This is a historic decision, as it is the first time that the EU executive has formally acknowledged the affordable housing shortage crisis. This is a problem that is well known and described in Poland. According to Eurostat, as many as 52.9% of our compatriots aged 25 to 34 live with their parents. At the same time, for 41% of surveyed Poles between the ages of 18 and 30, buying a flat appears to be a completely or almost impossible scenario.

When it comes to pessimism on this issue, we are not alone in Europe, and soaring purchase and rental prices are all to blame. As reported in the UK newspaper The Guardian, between 2010 and 2022, real estate in the EU became 47% more expensive on average, in the extreme case of Estonia reaching a staggering 192% during this period. The rental market has not fared much better, where costs have increased by an average of 18% and by an alarming 144% in Lithuania. As a result, for many households, accommodation-related expenditure has exceeded 40% of the household budget. At the same time, it has become an insurmountable challenge for many young Europeans to secure accommodation.

According to the EC chief’s vision, the remedy for the difficulties outlined is to create a European Plan for Affordable Housing. The politician also anticipates that Jørgensen will establish a pan-European investment platform to fund the construction of affordable housing. Additionally, he is expected to collaborate with Vice-President Ribera to revise state aid rules in a manner that enhances the energy efficiency of buildings and promotes the development of social and community housing.

- A Pole will lead the budget

Poland’s representative in the ‘new’ European Commission will be the former Permanent Representative of the Republic of Poland to the European Union in Brussels and a long-time close associate of Prime Minister Tusk, Piotr Serafin. As Commissioner for the EU Budget, Anti-Fraud and Public Administration, the official will focus on negotiating the upcoming EU budget, the Multiannual Financial Framework 2028-2034. His responsibilities will also include oversight of the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF). This is the second time this portfolio has fallen to Warsaw, previously the same post was held by current MEP Janusz Lewandowski between 2009 and 2014. It can be assumed that, through his role, Serafin will have the leverage to influence the allocation of budget funds earmarked for Poland, including funds for the areas most relevant from our perspective, such as cohesion policy or agriculture.

In conclusion, although the proposed composition of the College of Commissioners cannot yet be considered final – the candidates still face hearings before MEPs, potentially difficult especially for the politicians put forward by Viktor Orbán and Giorgia Meloni – its current shape suggests that the European Commission is trying to adapt its structure and composition to the challenges most frequently raised in the public debate. This is demonstrated by the establishment of a dedicated position focused on housing and the attention given to the issue of unfair commercial practices by Chinese platforms.

It is certainly positive to take a course on competitiveness and to acknowledge the growing distance between the European Union and China and the United States, as pointed out by Mario Draghi. However, some of the recommended ways to reduce it may be questionable. Of particular concern may be the reaffirmation of commitments under the European Green Deal, which in some fields formulates overly ambitious climate targets, completely ignoring the specifics of countries such as Poland and thus posing a serious threat to their economies. On the other hand, hope for reducing the intrusiveness of the green transition comes from the announcement of the implementation of initiatives such as the Clean Industrial Deal. It is also worth looking at any programmes and funding for the development of the most innovative technologies, including those related to artificial intelligence and space exploration.

ZPP Newsletter

ZPP Newsletter

Recent Comments